I overheard a conversation recently between parents, their child and a teacher. The child was struggling with structuring a piece in a particular genre of writing. The parents and teacher both told the child to practice, but neither offered the essential structures required to master the writing genre. The parents nodded in agreement when the teacher said, “Practice makes perfect”. The mother looked at her blank-faced son and said, “Yes, as I always say, practice makes perfect!”

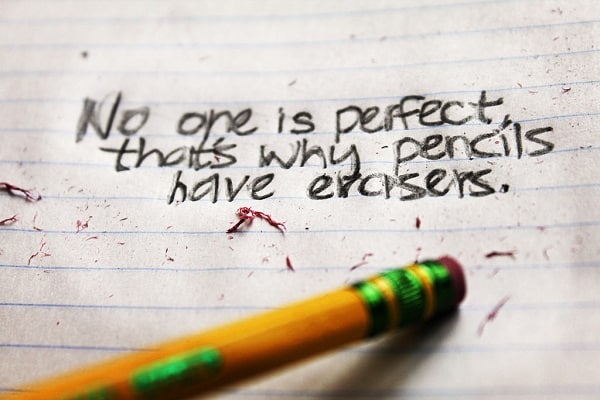

The only problem is – the adults here were wrong.

Practice makes good enough

The use of idioms, maxims and slogans – such as “practice makes perfect” – as a means of imbibing a message are, in my opinion, often almost wholly useless and possibly even psychologically dangerous.

Perfection is a suitably nebulous and subjective concept to frame one’s efforts around. Each child’s concept of what is ‘perfect’ is informed by the views of the “assessor of perfection”, the adult.

Since the concept of perfection is generally a subjective or personal one, it leaves a child at a loss as to what to attain other than something that is worthy of approval. What a strange way to imbibe encouragement: “Keep trying until I approve.”

It is obvious that practice is required to master skills and/or attain a level of understanding in a particular area of endeavour. This includes academic pursuits, art, sports, etc. Practice does lead to attainment and improvement and in the process, confidence building. Further, it may lead to some personal satisfaction and feeling of achievement. However, uncoached, it will not lead to “perfection”. Actually, even coached, it will not lead to “perfection.”

This is easily exemplified. Think of the highest achieving person in any field. Ask yourself whether the person is always peaking. That is, do they attain your own perception of perfection every time they do something related to their field of expertise?

The answer to this question every time, for any realist is “no”. Sometimes yes, usually… maybe. Always? Absolutely not. Otherwise what would be the point of any form of competition? The premise of competition is that a person’s “perfect” at a point of time is rewarded, and this will vary over time.

The highest achieving exemplars are not perfect, though we may see moments of perfection within the elitism of their performances. Why then should we impose some standard of “perfectionism” onto children? And why for routine or mundane tasks such as writing an English essay or creative writing piece?

What is perfect anyway?

A definition of “perfect” includes factors such as “as good as can be”, “qualities that meet the highest standards possible” and “features that are flawless”. The real question is: why would anyone aspire to such things when there is no objective standard against which to measure perfection? By definition, perfect is humanly unattainable.

For me, the person limping with each painful step along a pavement, in recovering from a car accident, a week earlier is walking bravely and perfectly. Similarly, the awkward legs-bent cartwheels of a child in a playground are the perfect expression of joy – though not resembling a cartwheel performed by an elite gymnast.

The child who tries their best to write an essay, in the absence of structures and guidance, has written the perfect piece.

Practice and what is attainable

In terms of practice, the aspiration should be, at least initially, “good enough.” That is, we should be affirming the idea of practice in so far as it leads to a reasonable enough standard to master the task at hand. If a child can go further, great.

The basis of “good enough” is an excellent springboard to “better” and “how far can I go with this?” However, the outset is not cast in the inevitable feeling of failure that “perfection” encompasses.

If a child cannot get to a point of “good enough” then the purpose of practice will never be lost, as it focuses on processes rather than outcomes.

In an educational and parenting context, practicing for perfection leads to an incapacity to take risks. After all, why try if “perfection” is the only sign of effective practice? This is most evident in schools and families where bright children are underachieving. Often, though not always, this child is the second or third born child with a very high achieving older sibling.

Alternatively, it can be the older boy with a high achieving younger sister, or vice versa. The permutations are many but the parameters are the same. The parent or educator’s expectations and ideals have been internalised by the child to the point where perfection matters more than trying, where success or mastery is measured in terms of what others can do, and where what is done is prioritised over how the child feels.

If a parent or teacher must say anything – it might be better to role-model a capacity to critique the effect of off-hand statements on a child’s self-confidence.

To the parents and teachers who say, “Practice makes perfect” I ask this. Why say something so perfectly flawed?

Practice makes perfect?

The idea of ‘perfection’ we seek in our kids’ endeavours from constant practice is deeply flawed

Reading Time: 4 minutes