Fact: Female desire pervades South Asian music, dance and poetry, particularly that from the Indian subcontinent. Whether written by women, or by men, the female voice is the dominant mode of expressing sexual desire and longing, for gods, men, and other women.

We became struck by how Indian classical music is still replete with this same female voice. And often, it is a voice that is demanding and sure of its agency, and its right to sexual satisfaction.

Even in the beginner lessons, we find the swarajathi, Raravenu Gopabala, voiced by a heroine, who asks Krishna to ‘come’ and to ‘take her’. The song isn’t unique. In the well-known Tamil composition Alaipayuthe a heroine asks Krishna to “take her to a lonely grove and fill her with the ecstasy of union”.

These songs aren’t exceptions – we have the female voice of desire everywhere in Indian music and dance, that is the simple truth.

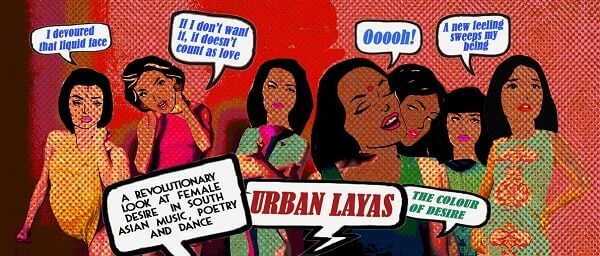

So we decided to create a music and dance concert, The Colour of Desire, that centred around female desire, weaving in these different voices and translating and asserting the female-centred sexuality of our musical tradition.

And yet Indian culture is conservative and repressive when it comes to female sexuality. It’s by now a cliché of outsider observation that the people that produced the Kama Sutra (which, by the way, is very clear on the need for women to experience sexual pleasure) are now sternly moral about sex, sex before marriage, and sexual pleasure in general. Also, sex, as a domain in popular Indian culture today, belongs to men. It is something men consume. The way women ‘contribute’ is by making themselves available, objects of desire, rather than equal participants who have a right to be sexual because they want it and enjoy it. The recent controversy around Lipstick Under my Burkha underscores that women who are sexual are so scandalous and unacceptable that this is something that we can’t even talk about or see on screen.

The popular Carnatic musician Prince Rama Varma, once joked about how “it’s better not to translate” the 12th-century poet Jayadeva, whose songs are a favourite of classical musicians and dancers. Jayadeva wrote intensely, graphically erotic poems in – you guessed it – the female voice. So there’s a double standard: we sing erotic material, but we overlay it with a patina of devotion, and deny or prefer not to imbibe its eroticism, especially its clearly female eroticism. Ignorance, apparently is bliss. This is dangerous because we risk forgetting the rich history of this eroticism in our culture. A collective amnesia in effect rewrites our history with a different story, a story that cements a particular strain of patriarchal repression that denies women sexual agency. This re-written, historically inaccurate, stiflingly repressive story is then in turn used to justify the sexual repression of women. And because we, as women, are the receptacles of ‘culture’ and the barometers of morality, an interest or expression of sexuality is seen as threat to this falsely re-imagined fabric of culture. Gaslighting, anyone?

Why does this matter?

In patriarchal culture – a culture which is still dominant in varied forms in most parts of the world, including Australia – part of the way women are repressed is by having their bodies – the physical body and the images of their bodies – labelled, categorised, objectified and corralled in a way that simply does not happen to men. Women also experience gendered violence on a staggeringly, disgustingly disproportionate scale, and this often includes sexual violence. One in two women in India are said to experience domestic violence. In patriarchal environments such violence is very easily dismissed or rationalised using ‘culture’. The confluence of patriarchy and a constructed culture where women are denied sexual expression, freedom or control leads to a toxic situation where women are blamed for violence perpetuated against them because they dared step beyond the narrow definition of how ‘respectable’, ‘cultured’ or ‘moral’ women behave. Such victim blaming is rife in India; a court in India recently awarded bail to 3 students for sexually assaulting a woman on account of her “adventurism and experimentation in sexual encounters.” Conviction rate for rape in India is a dismal 25.5 % (compared to 46.9% for other crimes). Victim blaming and gendered violence are by no means uniquely an Indian phenomena; in Australia, one in four women has experienced physical or sexual violence at the hands of a partner and 1 in 5 Australian women has experienced sexual violence. Women experience violence in every sphere – at home, in public spaces, and at work, as the #MeToo campaign has shown.

To sing of female desire, to uncover its history, and to call it by its true name – is to assert women’s rights to sexual freedom, sexual expression, and sexual choice. And this is why we – ‘nice’ Indian girls and purveyors of classical music – must sing of desire.

I lie here weak and broken.

His sweet lips are soaked in the nectar that never sates.

Let me not wilt.

Andal, 9th century

You call me to bed, I don’t make a fuss.

But unless I want it myself,

It doesn’t count as love.

Annamacharya, 15th century

In this clear moonlight (that makes a day of the night,

I strain my eyebrows hard and look in your direction,

The mellow tunes of your flute come floating in the breeze…

My eyes feel drowsy and a new feeling sweeps my being

Come! Mould my tender heart, make it full and fill me with joy!

Come! Take me to a lonely grove and fill me with the emotions of ecstatic union!

Oothukadu, 18th century