COVID-19 has sent governments around the world scrambling to implement stimulus packages to encourage spending and keep their teetering economies from collapsing. Australia’s focus, including in the recently handed down Federal Budget, has been on incentivising businesses and facilitating welfare payments for residents and citizens. However, these measures overlook the broader community of international students, refugees, asylum seekers, working holiday makers and skilled temporary migrants that play a critical role in Australia’s economy.

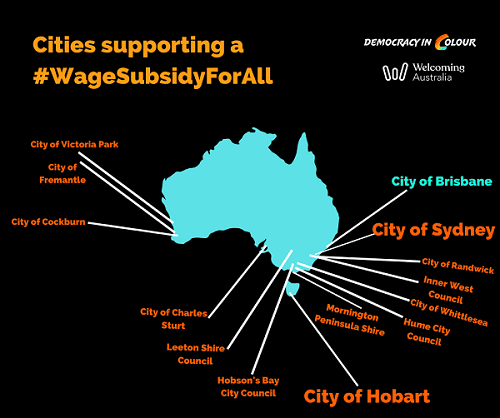

That’s why social justice organisations Democracy in Colour and Welcoming Australia, together with over a dozen participating local councils, have recently launched a new advocacy campaign pledging support for these workers to ensure no part of the community is left behind.

Speaking to Indian Link, Democracy in Colour national co-director Neha Madhok describes the joint “Nobody Left Behind” initiative as a necessary backstop to make up for failures in federal government policy.

The campaign, which has seen 14 local councils commit to providing funding or in-kind support for temporary visa holders, is also aimed at ramping up pressure on the Morrison government to extend wage subsidies to the 2 million people who are currently excluded from the government’s JobKeeper package. Critically, these workers are typically over-represented in industries that have been affected by COVID-19, particularly in the hospitality and entertainment sectors.

“Ultimately, ensuring people have access to social security is the federal government’s responsibility,” says Madhok. “Our elected officials who we voted for last year are responsible for ensuring that everyone who works here is okay. Even though temporary migrants can’t vote, they are paying tax, working incredibly hard to support themselves and their families, and doing so in lockdown situations in which the rest of us have been kept very comfortable. State governments have already had to fork out cash to try and keep people afloat, now it’s come to local councils to try do the same.”

READ ALSO: New English language requirement a hark back to White Australia Policy?

Madhok draws on her family’s experience of migrating to Australia in the early 1990s in highlighting the importance of social security in allowing migrant workers to ultimately flourish.

“We were really lucky because we were on a pathway to permanent residency, and had the protections of social safety net including Medicare and welfare, which meant my parents could do what they needed to do to survive. Dad getting a permanent job was what changed our lives,” recalls Madhok.

“But the lives of temporary visa holders stay [difficult] – in my case, my father had to work cash-in-hand jobs, while my mother’s qualifications weren’t recognised. Temporary visa holders in similar situations might have to become Uber drivers or take up other similar jobs,” says Madhok. “But because my parents were on a permanent pathway, which has been eroded over the last 20 years, that’s the reason I can be a middle-class person, go to university, and have the privileges of a comparatively very comfortable life. What would happen if my parents came to Australia just 20 years later?”

And for those temporary migrants who did migrate 20 years later and are living in Australia during COVID-19 today, the challenges can be overbearing.

“You hear stories of migrants living with 16 to a bedroom, eating once a day, lining up outside Melbourne city council and other places to access food, and people going without so that their kids can eat. It’s a really terrible situation,” says Madhok.

READ ALSO: Legally Brown: Championing diversity in the legal world

But the challenges span beyond Australia’s borders. Madhok recounts the story of an individual involved with Democracy in Colour: “Their family overseas lost income during COVID, and just like many people of colour across the country, they’re now working extra time to make sure their family back home is okay. It’s a really common story we’ve heard all across Australia where there are people who have to change their own lives even if they themselves haven’t been impacted by COVID in that way, but their friends or family overseas are absolutely suffering,” says Madhok.

With local councils such as City of Sydney, City of Hobart and City of Hume having already signed the pledge, Madhok and her team continue to pressure other councils with large South Asian populations who have yet to do so, such as the City of Parramatta. It’s a role that will prove even more critical given the deficiencies identified by Madhok in the recent Federal Budget, including as to social housing and wage subsidies for temporary migrant workers.

Madhok concludes with a call to action: “Unless we stand up and do what we can in our communities to call for a better world, then someone else will make that decision for us. If they do, they won’t make it with our best interests in mind, and people of colour will get left behind.”

READ ALSO: Changes in Australia’s permanent migration program for 2020-21