The charkha, a symbol of the power of self-reliance, industry and determination, still retains its followers and admirers, find RAJNI ANAND LUTHRA and SHERYL DIXIT

After trying his hand at Mahatma Gandhi’s cherished spinning wheel at the Sabarmati Ashram, Amitabh Bachchan, one of India’s best loved film personalities, wrote that ‘peace and serenity’ descended upon him. There was never a stronger modern advocate of the cause of using this simple, yet highly symbolic piece of equipment.

Gandhi himself had said of the spinning wheel, “Take to spinning to find peace of mind. The music of the wheel will be as balm to your soul. I believe that the yarn we spin is capable of mending the broken warp and woof of our life”.

Many symbols epitomise India’s independence from British rule, but the ‘charkha’ or spinning wheel is perhaps one of the most powerful signs of the values and aspirations of India’s Independence movement.

The wheel of history

The legacy of the spinning wheel is an ancient one, hailing back to the traditional role of women in Indian society. Women would spin as part of their daily routine, which would often become a social activity as they spun in groups and took the opportunity to socialise as well. Cotton and silk fibres were generally spun on the charkha, into cloth or rugs. The charkha was generally included as part of a bride’s dowry, when she left her father’s home for that of her husband’s.

British imperialism at its worst

During the colonisation of India, the British realised that growing cotton was a cash crop that could enrich their coffers. Cotton was grown in India, then harvested and shipped to Britain by the colonialists, where it was woven and spun into cloth. This was then shipped back to India and sold at unaffordable prices.

Naturally, Mahatma Gandhi opposed this blatantly unfair practice and propagated the concept of weaving homespun cloth on charkha in India, and wearing this in defiance of the price of English-made cloth. He made spinning on the charkha a symbol of the passive resistance movement in India, through this seemingly mild, yet powerful activity.

The homespun cloth was called ‘khaddar’ or ‘khadi’, meaning ‘rough’. Always one to lead by example, Gandhiji began spinning his own khadi on a charkha, and through his influence, thousands of Indians took to the spinning wheel, dealing a severe economic blow to the British.

Swadeshi self-sufficiency

The entire network of cotton growers and pickers, weavers, carders, distributors and charkha makers benefitted from this movement that represented self-sufficiency and interdependence on themselves as a community. Khadi embodied the dignity of labour, equality, unity and independence, as India took control of her indigenous industries. It employed millions from sowing of cotton seeds to spinning the final cloth to creating an outfit; it provided the basic need of clothing for the population, also creating a feeling of patriotic pride in the product. Indeed, Nehru called khadi ‘the livery of our freedom’.

Besides helping local business, this gesture heralded the start of a nascent ‘be Indian, buy Indian’ movement, as Indians began boycotting foreign goods and choosing locally produced ones instead. This was a significant boost to India’s fledgling economy. The ‘swadeshi’ (home-grown) movement had taken root, and was here to stay.

More than a message

Although it’s likely Gandhiji began the charkha movement to make a statement to the colonialists, he soon discovered the merit in spinning, as it aided him in silent meditation. It is recorded that he found the action of the spinning wheel soothing and pleasing to the psyche. Gandhiji spent many an hour placidly spinning on his charkha, engulfed in the silence of his own thoughts. To take this concept to the masses, Gandhiji also spun in public. It is said that since the traditional charkha was bulky and difficult to move, Gandhiji held a contest to design a charkha that would be compact, portable and easy to afford. The winner was the box design of the charkha, and history recounts that the accelerator wheel was his idea. Also, the role of spinning that was traditionally associated with women, morphed into an activity that could be performed with ease and relatively pleasing results by men too.

Embedded in Independence

So powerful was the influence of the charkha, that the first designs of the Indian flag created included the traditional spinning wheel, a symbol of self-reliance. However, a few days before India became independent, a specially constituted Constituent Assembly decided that the flag of India must be acceptable to all parties and communities, and the colour scheme, saffron, white and green were chosen for the three bands, representing courage and sacrifice, peace and truth, and faith and chivalry respectively. The charkha was replaced by the Ashoka chakra, representing the eternal wheel of law.

The flag of India is only allowed to be made from khadi, although in practice many flag manufacturers, especially those outside of India, ignore this rule. Some Indian currency has a charkha on it and even political parties use the charkha as their symbol to denote their patriotism.

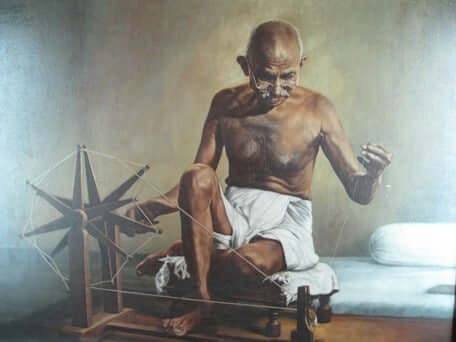

Iconic image

The black-and-white image of Gandhi with his spinning wheel that has become an iconic image of the Mahatma, was taken by American photographer Margaret Bourke-White in 1946, and published in Life magazine in 1948. Margaret Bourke-White said later, “It would be impossible to exaggerate the reverence in which (Gandhi’s) ‘own personal spinning wheel’ is held in the ashram”.

In notes accompanying the image, Bourke-White observed, “(Gandhi) spins every day for 1 hour, beginning usually at 4. All members of his ashram must spin. He and his followers encourage everyone to spin. Even M. B-W was encouraged to lay (aside) her camera to spin … When I remarked that both photography and spinning were handicrafts, they told me seriously, ‘The greater of the two is spinning.’ Spinning is raised to the heights almost of a religion with Gandhi and his followers. The spinning wheel is sort of an ikon (sic) to them. Spinning is a cure all, and is spoken of in terms of the highest poetry”.

Even though some of Gandhi’s contemporaries did not understand his obsession with the spinning wheel (Rabindranath Tagore thought the charkha and khadi movement were akin to a cult), it cannot be denied that it became an agent of change, by heralding the swadeshi ethos, recognising the dignity of labour, bringing in social and economic upliftment, and importantly, unifying the Indian masses against a common threat.

Modern mission

The charkha remains an icon of the swadeshi movement, and despite economic, industrial, political and social change, has never lost its popularity. Homespun khadi is still in demand despite mechanisation of the production process, and the charkha is still used to create wonderful, rare and unique pieces of clothing, rugs or other décor. Charkha spinners are sought after for their trade which, while not as aggressively promoted since the past 66 years, still retains its followers and admirers. Indeed, some are found here in Australia, keeping alive the legacy of the spinning wheel.

Gandhiji’s charkha and all that it embodies still lives on as a symbol of resilience, self-reliance and strength in a changing world.

The charkha in Australia’s Indian community

We may have the impression that the charkha is indigenous to India and its colonial history, but it certainly made its presence felt through exponents of the art.

For Dr Nana Badve, a much-loved member of Sydney’s Marathi community and the RAIN seniors group, the charkha was a lifelong passion until he passed away in 2010. He worked in the textiles industry for most of his life, and there is little doubt that it was his early introduction to the charkha at just 12, that influenced his career choice.

His daughter Swati Lele remembers fondly, “The founder member of the Spinners and Weavers Guild in Australia, the late Mrs Pat McMahon asked my dad if he would demonstrate the use of the charkha. This was the beginning of a rewarding journey for him as he conducted many workshops over 25 years around Melbourne, Brisbane, Newcastle, the Blue Mountains, Gosford and Sydney. In January 1989, he was a special invitee to the Melbourne Craft convention where he held a large workshop on spinning”.

Nana’s wife Sarojini Badve was always by his side, and a helper at the workshops. Nana not only owned many spinning wheels, but also sourced some 100 charkhas from India for spinners here.

Born in 1929 to a family much influenced by the Mahatma, young Nana was encouraged to spend some time spinning daily, like others in the family. He first learnt to spin cotton on a spindle, called takali. It was hard not to feel drawn towards the political struggle of the times.

“He stayed at Gandhiji-led ashrams and got involved in the movement for Independence,” Sarojini reveals. “In his early childhood, he enrolled himself as a volunteer at youth organisations and was a member till almost 1950. He attended many meetings addressed by Gandhiji and his contemporaries”.

In fact, with his charkha, Nana reminded many here of the great man himself. Sudha Natarajan, a close friend from the RAIN group, recalls, “Nana would often quote Gandhi: ‘Live simply, so that others may simply live’. These words ring so true today in these times of wasteful extravagance. Nana would insist that we need to simplify our lives. Following in Gandhiji’s footsteps, Nana even visited several Indian villages, where he encouraged the use of the charkha”.

Towards the end of his life, Nana would often ply the charkha for his RAIN friends.

“When he passed away, we made sure to display his favourite charkha during his memorial service,” Sarojini says. “His woven portrait of Mahatma Gandhi, which he made as part of his Bachelor’s degree in 1952, has now been donated to the Cavalry Hospital in Sydney. It hangs in the foyer there”.

And a charkha contest!

The charkha makes a regular appearance at one specific annual event here in Australia. The Teeyan festival held in the Punjabi communities of Sydney and Melbourne is doing its bit to keep the age-old tradition alive. Organised by the Indian Women’s Cultural Association of Australia, this festival, celebrated primarily by women, strives to provide a ‘cultural renaissance’ for women of Punjabi heritage now settled here. It was launched in 2005 by Harpal Kaur, Virinder Grewal and Amandeep Grewal.

“Arts, crafts, music, poetry and dance are all packaged into a day-long affair, with presentations and competitions in a variety of categories,” the Melbourne-based Harpal Kaur says.

One contest involves the art of working the charkha. The organisation owns four specially created Punjabi style charkha flown in from India, which are brought out for each year’s event.

“We provide the participants with cotton punis (rolls of carded cotton) which they have to spin into thread,” explains Harpal.

Judges note the time taken to spin the yarn, as well as the quality of the final product; the finer the thread, the better the quality.

Harpal Kaur says, “Our attempt is really to reconnect to our roots by having the older members of our community demonstrate our traditional arts and craft, and to encourage the younger members to try their hand at the traditional charkha”.

A number of young women have given the charkha a go at the annual Teeyan festival. While it may not bear much significance to their daily lives, their grandmothers in their day, would probably have been judged by their prowess at their charkha abilities. For them, it was an important skill of ‘cultured living’, and girls of ‘good upbringing’ were expected to be adept at it.

Over the ages, the charkha pervaded many aspects of the cultural life of Punjabis. Philosophers and poets from Bulle Shah to Guru Nanak used it as a metaphor for life’s exigencies.

This year’s Teeyan festival in Sydney is coming up shortly, and once again, Virinder Grewal’s cherished charkha will get a good workout.

The Powerhouse Museum

Another charkha sits in state at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney. A prized boxed charkha dating from the 1060s, it was donated by a fabric spinner of many years. Accompanying documentation claims a friend bought the item in Bombay for $4.00 and presented it to the donor as a gift. The donor approached the museum to see if it would acquire the artifact, and the gift was gladly received.

The Mahatma advocated the use of the charkha as a spiritual act, with the hope that its inherent attribute of fostering self-sufficiency characteristic would alleviate poverty and bring about much-needed social upliftment. And indeed, history proves that it did! This intended message of the charkha, to become self-reliant and to live more local and communal lives as a means of resisting the globalising power of corporations, is perhaps even more relevant today than it was in Gandhi’s time. It is hoped that the charkha will continue to inspire generations to come through its message of hope, humility and perseverance.

The e-charkha

In 2007, Indian inventor RS Hiremath produced a modified version of the Indian spinning wheel which harnesses the energy used to spin it and transforms it into electricity. Called the e-charkha, the device is now commercially produced by Bangalore-based firm Flexitron.

It is used in rural India where people are used to the idea of hand-spinning.

The e-charkha comes fitted with a dynamo which converts the kinetic energy generated by the spinning wheel into electric energy. The electricity thus generated charges a battery connected to the device. Two hours of continuous spinning can power an LED light for six to seven hours. This might not seem much, but in sections of rural India with no electricity, it is substantial.

The e-charkha costs between Rs 3000 to Rs 12,000, comes with a warranty of 35 years and is made of light material to make it more user-friendly.

The idea came to Hiremath as a child when he as he studied his grandfather’s charkha.

Cherishing the charkha

Reading Time: 9 minutes