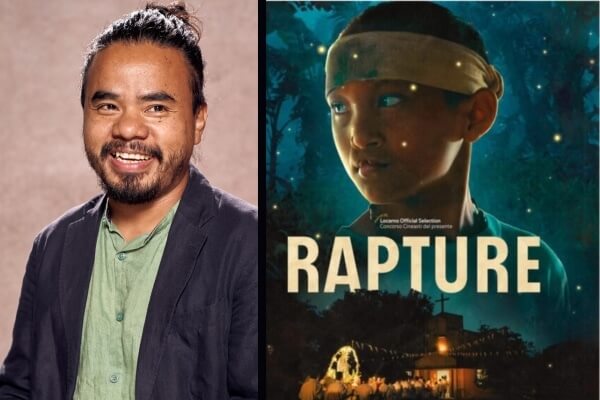

Dominic Sangma’s Rimdogittanga (Rapture) is a fascinatingly complex moral fable. Set in a remote village in Meghalaya – drawing from experiences of Sangma’s childhood – the film uses the trials and tribulations of the Garo community as a microcosm of India and the climate of fear that’s gripped the nation today.

The film uses the catalyst of an evil, unseen spirit that’s supposedly kidnapping people to delve deeper into how easily a community can succumb to paranoia, giving into the fear of others and rampant xenophobia.

Dominic was recently awarded the IFFM Award for Best Director (Critics Choice) at the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne for Rapture.

View this post on Instagram

The making of a trilogy

Dominic’s cinematic journey is deeply personal and rooted in his experiences growing up in the Garo community of Meghalaya. His latest film, Rapture, represents the second instalment in a thematic trilogy that began with MA.AMA in 2018. This trilogy is not a traditional series with recurring characters but rather a collection of explorations into different emotional and philosophical territories.

“I did not set out to make a trilogy,” Dominic reflected. “My first feature MA.AMA (2018) and then Rapture (2023) emerged from my own memories. Both these films are based on something I’ve closely experienced.”

“MA.AMA was about a death in my own family. My mother passed away when I was two-and-a-half years old, and there was this belief that she passed away because somebody did black magic on her,” he shared. This film was Dominic’s way of processing a profound loss that had haunted him from a young age.

In contrast, Rapture grapples with a different kind of emotional turmoil. “Rapture is about the experience of growing up with this constant fear of strangers and outsiders,” Dominic explained. “And against this backdrop, you have the Church prophesising about a ‘darkness’ that’s coming. So, I grew up in that environment of fear and people being afraid of the ‘other’.”

The film captures the pervasive anxiety of living in a community gripped by paranoia, using the fear of an unseen spirit as a metaphor for xenophobia and the alienation of the ‘other’. These films, Dominic believes, are his way of confronting and exorcising his personal demons.

“Both films were a kind of therapy for me – an attempt at articulating my own fears,” he said. “I had this feeling that I can’t move on and make another film until and unless I let go of this fear. These events that I experienced stayed with me and I needed to find a way to release them, let them out into the world.”

Looking ahead, Dominic envisions the final piece of his thematic trilogy exploring the concept of beauty. “MA.AMA was about longing. Rapture is about fear. And the next film in this trilogy will be about beauty. So, this is not a character driven trilogy, but rather, a thematic trilogy.”

How Dominic Sangma merged the personal with the political, and his motif of sight

In Rapture, the exploration of sight and perception becomes a central motif, intertwined with personal and political themes. The film’s protagonist, a young child, suffers from night-time blindness, symbolising the broader theme of visibility and invisibility that pervades the narrative. This condition reflects the limited perspective of the characters and their fear of the unknown, mirroring the community’s struggle with the unseen malevolent force.

“The idea of ‘seeing’ and sight in different ways is crucial to the film,” Dominic said. The mysterious spirit that allegedly kidnaps villagers serves as a metaphor for the anxieties that arise from the unknown. The Church wants the villagers to submit to its alien belief system for salvation, with the film critiquing how external belief systems and their clash with indigenous communities can have a devastating impact.

Dominic sees parallels between this narrative and the geopolitical context of India, where the struggles of the Northeast often remain unseen and unacknowledged by the rest of the country. Once you take a step back, you realise that this idea of sight and visibility applies to the current geopolitical context – where the rest of India refuses to acknowledge or see the plight of the Northeast region. The film thus becomes a metaphor for the larger struggle of visibility and representation, highlighting how marginalised communities can be rendered invisible in a broader national discourse.

“I started writing Rapture in 2018, working on it parallelly along with my first feature. The atmosphere in the country at the time was a big influence on the writing of this film,” he said.

Dominic’s aim with Rapture was to address the grassroots level of these fears. “I wanted to tackle this fear that had come back in the country on a grassroots level. I wanted to tell the story of my village, about the ongoing conflict between the Church and the indigenous belief systems of this village community,” he said.

By blurring these distinctions, Dominic sought to provoke a deeper examination of what it means to be ‘othered’ and the irrationality of such fears. “I wanted to explore these supposed binaries – Outsider versus Insider, Spirits versus Humans, and Belief versus Non-Belief. Nothing is absolute in the film,” he added.

Beyond labels: Dominic Sangma’s fight to be seen as an Indian filmmaker

Despite the critical acclaim for Rapture, including winning the IFFM Award for Best Director (Critics Choice), Dominic faces ongoing challenges related to regional and ethnic identity. “First of all, it is difficult for Northeastern films to even be considered ‘Indian’ films, you know? Because of how we look, there is this xenophobic perception that we are not Indian,” he lamented.

This perception leads to the pigeonholing of films from the Northeast into specific categories that can limit their reach and impact.

“And on top of that, when you are a regional filmmaker like I am, your film gets clubbed into the Indigenous Language section, or the Northeastern Language section,” he said. This segregation can be limiting, as it implies that such films are only relevant within certain contexts and not part of the broader Indian cinematic landscape.

Dominic argues that films from the Northeast, including Rapture, represent more than just regional concerns; they are a part of the larger Indian narrative. “What people fail to understand is that when any film – whether it’s a Garo film such as mine or any other – travels from India to the world, it is not representing one community alone. It’s representing all of India. These films are seen as Indian films. My film is an Indian film,” he asserted.

He challenges the notion of being confined to regional labels and calls for a more inclusive understanding of Indian cinema. “That’s why, I think that if you believe that my film only belongs in the Indigenous Language section where there are only a few other films, then it really restricts the audience. I don’t want to do that. I don’t want my film to be perceived that way,” Dominic said.

He advocates for a broader recognition of the diverse voices within Indian cinema, arguing that such films should be evaluated on their own merits rather than through the lens of regionalism. Dominic’s vision extends beyond merely asserting the identity of his films. He emphasises the need for a collective effort among filmmakers from the Northeast to resist reductive categorisations.

“I keep telling other filmmakers and friends from the Northeast that we should collectively refuse and deny such labels. We are from a small community, but it’s important that our voice is heard,” he said.

By challenging these limiting perceptions, Dominic hopes to pave the way for a more nuanced appreciation of regional cinema as an integral part of the Indian film industry.

Dominic Sangma’s Rapture first came to Australia in June this year for the Sydney Fim Festival.

Read more: IFFM 2024 blinds Melbourne with star power