Given the backdrop of Australia’s shameworthy past regarding Indigenous Australians, the exploration and deeper understanding of First Nations history and culture is an extremely sacred and necessary endeavour, carrying immense significance. This may be one of many reasons behind why we don’t often see cross-cultural collaborative pieces between First Nations People and other cultures. Yet this formed the basis of Bhoomi: Place & Belonging as part of the Gai-Marigal Festival, which, founded in 2001, aims to raise awareness of First Nations People living in the Northern Sydney region.

Through a composition of different pieces, Bhoomi sought to convey a dialogue between First Nations and South Asian voices through multi-modal art forms. Though I wasn’t sure what to expect, I was extremely impressed. Bhoomi beautifully traversed the intersection between both cultures in a way that was meaningful enough to stir emotion and provoke conversation but delicately, to ensure the appropriate level of care and respect was given. Through the musical pieces, spoken word renditions, poetry and subsequent panel discussion, Bhoomi: Place & Belonging gently surfaced tough issues but still left the audience with a greater appreciation for the importance of cross-cultural conversation.

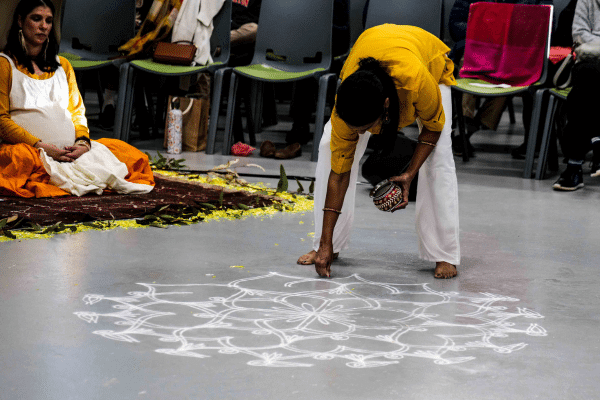

The universality of pain and its role as a common feature in the history of both cultures was brought to the fore, especially through the pieces Kolam and Breathe. In Kolam, an excerpt from Song of the Sun God was read by the author, Shankari Chandran, while another artist created a kolam (a ritualistic ground artwork of intricate patterns using rice or flour). The combination of art forms powerfully illustrated the connection between individual and homeland and how pivotal this is to identity. The words told the story of dislocation from land during the final years of the civil war in Sri Lanka, and the pain was amplified by the sombre melody played on the veena in the background. In a different way, Breathe similarly emphasised the power of connection to land through poetic description of its elements – rivers, rain and Country. While the piece beautifully conveyed the richness of ancestry held within nature, it also alluded to how connection to Country has painfully changed through generations, and the impact this has had on sense of self.

Amongst the commonalities, the differences between both cultures should be noted, particularly with respect to privilege. The histories and journeys of First Nations People are vastly different to those of South Asian immigrants. A pivotal question was raised during the panel discussion; as South Asian diaspora on First Nations soil, how can we resolve the tension of our privileged upper caste views when we collaborate and make art with First Nations People here? Indu Balachandran, one of the artists and panelists, addressed this well, clarifying that this is a deeply complex question without any binary answer. It is a personal journey that needs to be undertaken by each of us. We need to acknowledge what that privilege means in different places and how it can be used to build powerful collaborative communities.

Driving this home even further were Tristan Fields’ words, “When you are working in someone else’s country, you are working in someone else’s world. Our intentions are always good, but at the end of the day we aren’t always going to get it right. It is okay to make mistakes, and it is about practice and being able to want to create the change”. This was deeply compelling, as I, like many others am often cautious around initiating these conversations for fear of getting it wrong. This position however has meant that First Nations cultures are often only explored in siloed ways, which sometimes creates more distance between us and our appreciation of it.

Bhoomi must be commended for showing us that there are forums where the commonalities between these cultures can be explored in open and safe ways. It was clear that this was not done lightly, and that it was the culmination of many conversations and deeply personal journeys of the artists. The pieces selected were carefully curated to invite us to hear and share in meaningful stories that held cultural, emotional and historical weight.

More importantly, for the artists, through spaces like these, they are able to take traditional stories from where they come, and apply that to a contemporary setting, to not just tell their story, but to re-imagine them and invite others to be part of the narrative as much as they want to be.

While nothing will take away from the significance of preserving history and tradition through our stories, it is refreshing to see that we can be open to new conversations where these may be re-shaped to focus on shared futures.

Read More: Bhoomi: Mother Earth Speaks – A music and dance event