While the result of the ruling party in power is clear, the Senate remains a hotbed of clashing objectives, writes NOEL G DESOUZA

The 2013 elections in Australia have resulted in a ‘people power’ change, given the widespread support that those standing for a new government received. It was done through the ballot box and an individual’s right to vote. That meant that aspiring politicians had to play by the rules of the established system. This has been best demonstrated by the motley collection of minor parties in the Senate. The Labor Party lost the election by 3.5%; in contrast, when Howard got elected in 1996 it had lost by 5.8%.

‘People Power’ can manifest in different ways. In 1986, President Marcos of the Philippines was overthrown by sustained demonstrations (said to be by up to two million people) with the support of the army and the Catholic Church. These latter organisations had once supported him during his long reign which was marked by corruption and disregard for the rule of law. The demonstrations ended with the installation of President Corazon Aquino, whose husband Benigno Aquino was gunned down at the Manila airport when his plane touched down after a well-publicised return to challenge Marcos. That was the last straw in the patience of the people.

In the last few years, there was an attempt to emulate a similar strategy in New Delhi. There were demonstrations centred around the figure of Anna Hazare, a supposedly devout and honest man. The claim that Hazare was a personage above politics and highly moral has been disputed and put to rest.

Changing a government through mob agitation can be interpreted as undemocratic, if democracy and the rule of law still prevails in a country. India is democratic with a well-functioning judicial system. Loud shouting and unruliness cannot be allowed to engineer regime change. Subsequent events have vindicated the democratic nature of India.

In Australia there was a hint of the ‘large demonstrations’ strategy when party leaders (mostly Liberal) were photographed with placards behind them. That was a simple but effective way of getting one’s message across. Strangely, the Labor Party did not use a similar strategy.

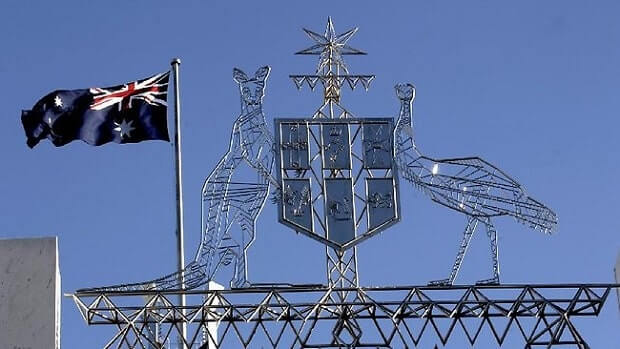

In Australia, for a government to wield close to absolute power, it has to control both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The last few governments did not control the Senate. The Senate is a good place to have allies for a party in opposition, but it becomes troublesome for a party in power. When a party wins power, one often hears talk about reforming the senate. That is a virtual fantasy because that would need a referendum, and Australia is notorious for rejecting referenda.

The Greens have held the balance of power in the Senate till now, but their vote has reduced (by 3.3% to 8.4%) and they will lose that control after mid-2014, because their numbers might be reduced by two senators. Green Senator Sarah Hanson Young’s vigorous defence of refugees raises the question: Which Australian group was she supporting? Refugees do not have a vote until they become citizens, as until then, they are foreigners. Nevertheless, the Greens keep control of the Senate till the middle of 2014. So till then all controversial legislation such as changing or abolishing the carbon tax, could get blocked.

After mid-2014 a new set of alliances will come into play in the Senate. There are going to be several small parties that need to be wooed to enact promised legislation. The motley collection of parties and individuals includes Palmer’s United, Katter, Pauline Hanson, Motor Car Party and Sex Party.

Palmer has effectively played the Australia card. He joyfully sang to his followers that ‘We are all Meat Pies’, meaning thereby that we are Australians independent of foreign influence and having our own symbolism. Palmer’s Party extended its reach even into Tasmania by unexpectedly getting 20,000 votes.

In the UK, there are limits to the power of the Upper House (or the House of Lords) in rejecting bills. Financial bills are approved even though the Upper House may not be happy with the proposed measures. In Australia, like in the USA, full approval by both houses is required.

The Australian people have changed the government, but burdened it with a non-compliant Senate. The change has taken place peacefully and is in stark contrast to the mayhem that characterised Middle Eastern politics at the same time.

People power leads to split result

Reading Time: 3 minutes