Tell us about your novel Daisy & Woolf. What was the inspiration?

Thank you, Rajni. It is a novel that explores the life of an Anglo-Indian woman, a minoritized character in Virginia Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness novel, Mrs Dalloway. Daisy Simmons plays an important functional role in that novel since Peter Walsh returns to England after five years in India for the purpose of arranging her divorce, supposedly so they can marry. Yet she is a footnote, and disturbingly, her mixed race has not been recognised by scholars or Virginia Woolf enthusiasts, though she is described as ‘dark’, ‘vain’ and ‘adorably pretty’. Peter is from an Anglo-Indian family; his references to India are derogatory, reflecting internalised projections of racial supremacy and scorn.

The novel follows one day in Clarissa Dalloway’s life. Although her past is tunnelled into the novel’s fabric, it’s as if all time has stopped for Daisy. Her rich and complex past, and indeed her future is absent from the terms of Woolf’s fiction. Instead, time becomes an aesthetic motif, a presentism for the privileged Tory socialite and her elite circle. They discuss ‘international’ (read: ‘imperial’) events and India’s caste system, the ‘coolies’ beating their wives up. Such fragmented details distort the status of India making the centre of London seem unduly civilised.

I wanted to reclaim Daisy’s past, to let the reader see her family, her home life, the way she and her cousins are teased by Brahmins, the pre-independence racial conflicts that continue today in an India that has staged its global presence since the 1920s. I wanted to show how narrative itself can be a form of silencing. When you consider the production of a novel, factors such as the marketing and publishing of books, there is a bias favouring the framing of ‘nation’. Characters who lie outside the borders are often reduced. This is problematic for Anglo-Indians whose identity has devolved between national and cultural imaginaries.

What was your research process?

I read diaries, history, and certain researchers were very helpful. It was harrowing to read extensively negative descriptions of my community and to recognise patterns of emotional and psychological trauma in my family that I had not previously aligned with colonialism’s crimes. It is difficult and retraumatising to speak of these things. As Indians we have normalised this intergenerational trauma, the historical displacement of mixed-race Indians, the orphanages, pastoral education, the Railway colonies and ghettos and the regulatory class control. Historically, the search for an Anglo-Indian homeland included Tasmania as well as McCluskie Ganj. One Australian researcher I’ve read states that 4% of Australian Indians identify as Anglo-Indian but the figure seems to be higher.

There has been so much pressure on mixed race Indians to assimilate, therefore, not to reflect too deeply on the threads of their heritage. Yet as humans the ability to trace our roots and speak our story raises our human consciousness and contributes, to a more tolerant inclusive and less ableist world.

How would you place Daisy & Woolf with other novels about Anglo-Indians and Eurasians?

In colonial fiction, Anglo-Indian and Eurasian characters were mostly stereotyped as morally lacking. There are few Anglo-Indian female characters with psychological depth and agency. Olivia in Heat and Dust by Ruth Prawa Jhabvala is a notable exception.

The history and culture of Anglo-Indian women, sits awkwardly in the matrix of the Indian diaspora and its imaginary. We have Bharati Mukherjee’s Jasmine who relocates to the US; Arundhati Roy’s Ammu who divorces her husband and loves a low-caste man, and Ismat Chughtai’s Lihaaf, breaking and queering the heteronormativity of our fiction. Themes of gender equality and isolation have been explored, but with a tendency to shun what is considered ‘colonial baggage’.

Mina the contemporary narrator, has to navigate her own fraught experiences of marginalisation. Are there autobiographical elements to your novel?

My ancestry is Goan on my mother’s side and Anglo-Indian on my father’s, so I have experienced colonial resistance, the loss of language, culture and invisible barriers to a dual cultural identity throughout my life. I understand this subtle stigmatisation which was founded in names.

When my family left India it was survival thinking. Like many Anglo-Indians they had emigrated first to East Africa and then, following independence to the United Kingdom. I will always be appreciative to Australia, the country where they were able to settle, and especially to First Nations people. When you research and read, however, it does make you wonder what ‘belonging’ means. On paper their journeys involved geographical distance and cultural displacement. Perhaps more significantly they were also navigating ambivalent administrational markers of ethnicity. The term ‘country born’ was used until 1800 with ‘half caste’ still being referred to in official documents in 1827. The term ‘Anglo-Indian’ was used for social purposes to distinguish Europeans and Indians; ‘European British Subjects’ was used for military and defence purposes, and ‘Statutory Natives of India’ was used for occupational purposes with ‘Indo-Briton’ being an older term in circulation.

How is Daisy & Woolf relevant for today’s political fabric?

The constitutional laws and measurements which have determined citizenship, nationality and agency have been based on dubious census statistics, partly because of slippery definitions of who is Anglo-Indian. From 1911 to 2019, when the 104th Amendment Act removed reservations in education and for parliamentary representation for Anglo-Indians. In Australia until 1973 we had the White Australia Policy.

Undoubtedly, this has been a community that has its own culture, one which has contributed significantly to India, and which we should embrace and celebrate as legitimate citizens.

As a novelist and poet, my work speaks to the disenfranchisement and trauma, but fiction is restorative. Writing from a ‘minority-in-a-minority’ perspective is both a gift and an act of reclamation. It is not enough to immigrate to Australia and take on a career. The search for true dignity comes from culture, from imaginative weaving, from walking with our stories through lines of maternal and paternal heritage rather than across the official limits and classifications of the ‘nation’.

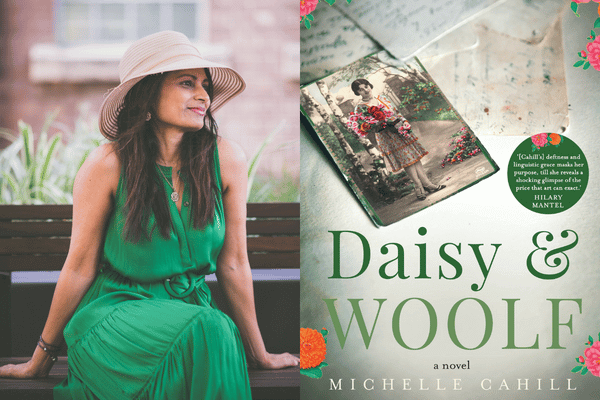

Michelle Cahill is a prize-winning Australian novelist and poet of Indian heritage. She won the UTS Glenda Adams Award for Letter to Pessoa and was shortlisted in the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards for Vishvarupa. Daisy & Woolf is published by Hachette.

READ ALSO: Relatively True: Stories of Truth, Deception, Post-Truth