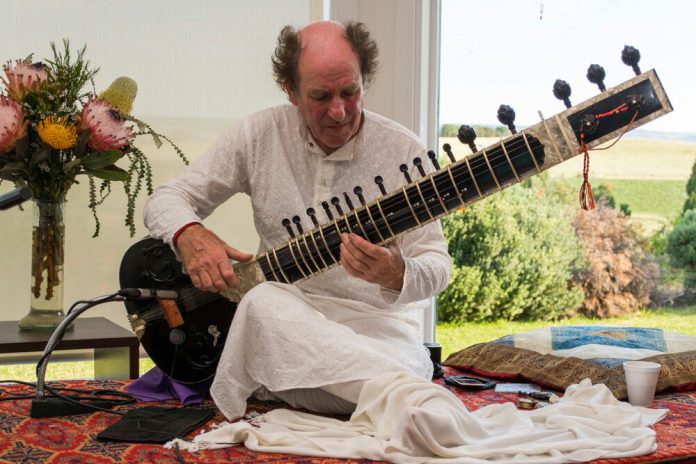

As a composer and teacher of classical guitar many years ago in Sydney, I once came upon a strange instrument at Ricordi’s music studios where I taught. It intrigued me. It was, I later found out, a sitar. There was not a lot known about the music of other cultures then.

At that time I was looking to introduce an element of improvisation into classical western music from Middle Eastern and Indian systems. As luck would have it, sarod player Ali Akbar Khan chose to tour Australia at the time. He was closely followed by Nikhil Banerjee, sitarist from Kolkata, whom I met and asked “How does Indian music work?” I was told that the only way to learn the principles is to learn by playing the music. I was encouraged to travel to India to learn it from the maestro himself, Allauddin Khan of the Maihar gharana – Guru of both Ali Akbar Khan and Nikhil Banerjee.

I still had Middle Eastern Oud and Baghdad on my mind, but since India was closer to Australia, I decided to try out sitar or sarod first and thought if I didn’t like that then I’ll explore further. Iraq never got a chance!

I arrived in Maihar in Madhya Pradesh in the late 1960s with a recently bought sitar in tow, with no thought-out plan. I enrolled in Allauddin’s music school where older students would teach younger students. Allauddin was in his 90s at the time, known for his moody outbursts, and no longer in active teaching.

Somehow he perceived the passion in me and magnanimously agreed to teach me on condition that we keep our lessons private. I visited his home discreetly by rickshaw, arriving at odd hours when not many people were around. My riaz (practice) would start at four in the morning and often continue until late in the night.

I did not feel I was a stranger in a new country.

On the contrary, I became fanatical about the music and got addicted to it! It was no less than any drug…I could never cease to be surprised and wanted to go to the next level and the next. I got motivated with my own success at learning. The more I played, the more I learnt and became adept. I had simple khana peena, chillies fried in batter, in between the practice sessions but no rest. People in India are used to siesta after a big lunch but I would not sleep. Instead I would practise.

My environment, different from that of my upbringing, held so much fascination for me. I enjoyed the novelty. Being involved in such music of course was a kind of spirituality, a ‘Naad’ Yoga to me. I had little desire to travel further. I was living my dream in that small town… which had the odd dacoit around! In fact, the leader of the dacoits – a tall, fierce man with a big moustache and a music lover, was a regular at the mehfils where I played sitar. I didn’t know much about his pursuits and cared even less.

In 1970 I went to Calcutta to attend Nikhil Banerjee’s concert and there I met another influential musician Pundit Radhika Mohan Maitra, who had a great impact on me. His English was good and I enjoyed his company and his direct teaching style. Music was addictive but by the same token I had to make my living to sustain myself. Eventually I decided to go to Europe to teach and make some money but returned to India not long after.

I moved to Kolkata in the final years of Allauddin Khan’s life where I learned under Pundit Radhika Mohan Maitra, the eminent sarod maestro of the Shajahanpur Rampur gharana. I liked Pundit Maitra’s refreshing, logical and generous approach to teaching. It had an incisive influence on me and my style of music. After Maitra’s death many years later, I received musical guidance from many eminent Indian musicians of different gharanas, including Kashinath Mukerjee, Bimal Mukerjee, Prabud Chatterjee, VG Jog and Pandit Arvind Parikh of the Etwar gharana of Ustads Imdad Khan, Enayat Khan and Vilayat Khan. Each of these influences have given me a rich foundation on which to build my own evolving style. Imdad Khan and Vilayat Khan use a vocal style to play instrumental music. As far as music is concerned, I’m still learning; you never stop learning.

In Kolkata I met my current wife who was from Adelaide. She probably didn’t know what she was taking on or getting into when we got together! A few years after meeting her we returned to Australia and I taught ethnic music at a tertiary level in Armidale, NSW first and then came to settle in Adelaide in the early ‘90s. I set up a school ‘The Music Room’ where I taught sitar and Indian music.

“I was once asked to play for a radio program and when the journalist contacted me and realised that I was not Indian…that was the last I heard of him”

I do feel that if I had been in Sydney, London or even Europe, where Indian music is widely accepted, I would have had greater success at teaching and serving music for a longer time. These cosmopolitan cities have a larger audience, who respect the nuances of classical music and are consequently helping the classical Indian musical tradition to survive.

In addition, while audiences and arts organisations generally accept Indian people playing Indian music, they are often unsure about how proficient an Australian can be! I was once asked to play for a radio program and when the journalist contacted me and realised that I was not Indian…that was the last I heard of him. Without any explanation, my program was cancelled.

Sadly, very few, if any, Indian-heritage people in Adelaide are interested in classical music. I would like to express my regret at the indifference to this beautiful art, partly due to changes in people’s musical taste and partly due to our hectic lifestyles. Such music thrives well in other countries like the UK, Germany, France, Italy and the US. It might be easier to live in Europe or London but Adelaide is my home – it’s just disappointing that the audience for this classical form is so restricted.