In late September 1945, at the end of World War II, Lt F.O. Monk of the Australian Army helped rescue a group of Indian soldiers held as POWs by the Japanese Army in New Guinea.

“It was heart-wrenching,” Lt Monk wrote later. “Ten of these poor fellows were lined up. Some were sitting because of the sores on their feet…. but were all rigidly at attention despite their rags and pitiable condition. In charge was a smart-looking man, Jemadar Chint Singh, also in rags but with the most military bearing who marched up, saluted, and said, ‘Sir, one officer, two NCOs and eight other ranks reporting for whatever duty the King and the Australian army requires of us’. I found it very hard to reply to him. I still feel much emotion when recalling it.”

They were the last survivors of a group of 600 Indian prisoners at the camp.

Today, more than 75 years after that rescue, we are learning the story of the ‘smart-looking’ officer Chint Singh for the first time in a new book just released.

It is written by his son, Narinder Singh Parmar, who has lived in Australia for over 30 years.

AT A GLANCE

- Chint Singh was one of eleven Indian soldiers who survived a brutal Japanese POW camp in New Guinea. They were rescued by an Australian army unit in 1945.

- Chint became chief witness at an Australian War Crimes Commission investigating Japanese atrocities. His daily diary entries were presented as evidence.

- These diary entries have been put together in a book released recently by his son, the Wollongong-based Narinder Singh Parmar, titled Chint Singh: The Man Who Should Have Died

Parmar’s book, Chint Singh: The Man Who Should Have Died is an extraordinary story of survival in the face of extreme hardship and violence. It does not end at the rescue by the Australians. Indeed, the story becomes even more remarkable after that.

In the months following, Chint Singh became chief witness in the Australian War Crimes Commission investigating atrocities committed by the Japanese Imperial Army. While he stayed back in Australia to testify, his comrades, flying back home, all perished in an air crash.

Chint Singh became the sole survivor of 5000 Indian POWs taken by the Japanese.

“We should have killed him,” one of his Japanese captors muttered at the trial.

Narinder Singh Parmar observed, “My father was a man who should have died. He survived torment after torment, and by a strange twist of fate, escaped that final fateful blow which took the rest of his company.”

That strange twist of fate – the War Crimes Commission and how Chint Singh came to be in it – is one of the many astonishing aspects of Parmar’s book.

Much more than a personal account of his father’s story, the book records a part of India’s military history about which very little is known.

Revealing facts about India’s involvement in World War I have come to light in the past decade; this book, it is hoped, will begin the interest in unearthing stories about the subcontinent’s participation in World War II.

Yet for Parmar, it is more than just a book. “I see it as my father’s desire being fulfilled – he wanted the world to know this survival story.”

(In a particularly despondent moment amidst the swamps of New Guinea, Chint had recorded that if he lived, he would tell his story.)

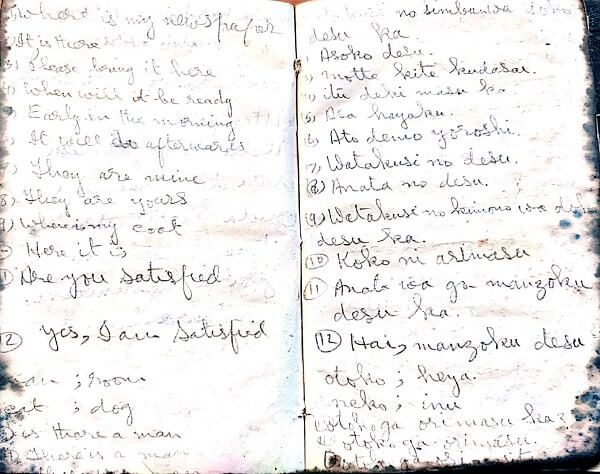

Parmar’s book is in his dad Chint’s words – recreated mostly from his diaries, and the notes he jotted down on whatever paper he could find, including the wrappings on food tins.

The earliest notes come from 1941, when Chint was deployed to Malaya. After the fall of Singapore in 1942, Chint was among the thousands of soldiers taken prisoners. Shipped to New Guinea, Chint and his men were put to work in manual labour through swamps and jungles, under the worst possible conditions. Chint recorded starvation, disease, regular beatings, insults, race hate, stealing food to survive, and eating lizards, grasshoppers and snakes.

Records show Chint asking for relief for his men according to international law. It only resulted in further punishment. Men who escaped were dragged back to camp and beheaded publicly, or bayoneted.

Quite horrifically, Chint wrote of men who went missing, after which large quantities of meat were cooked in the Japanese kitchens.

His copious notes, diligently recorded, show dates and names of Indian men beaten or killed, and the Japanese men that committed these crimes.

These notes would become evidence later.

“They saved my father’s life,” Parmar remarked.

In his own retelling of the story, mentored by well-known Australian historian Prof. Peter Stanley, Parmar has added details of each soldier who is mentioned in his father’s diaries. He credits these details (including names of family members and the village they came from) to military researcher Adil Chhina, but they show that he has inherited his father’s attention to detail. They also reveal Parmar’s own dedication to ensure that the sacrifice of the men is duly recorded, and brought to the attention of the world.

Growing up, Parmar knew little about his father’s story – only that he had been a POW. “He never spoke of it to us, but I’d seen some old newspaper clippings, and had heard him speak occasionally at events at Rotary Club or Lion’s Club.”

It was in 1990, only months after he arrived in Australia, that Parmar met Kevin Deutrum, a government official who served in PNG. Kevin recalled seeing a memorial dedicated to Chint Singh. He had followed it through and found a document in a Port Moresby library, written by Chint.

“That was enough to motivate me. Through Kevin, I met Marsden Hordern, the officer who had arranged the rescue of my dad and his men in 1945. Turns out, he and my dad had kept in touch for years after.”

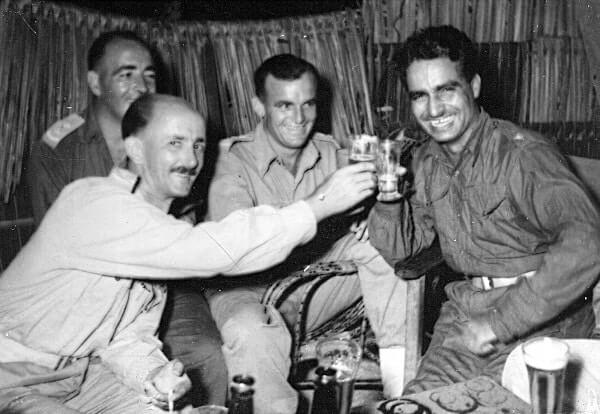

(The book records the growing bond between the two men as the Indian POWs recuperated in the Australian camp.)

Shortly thereafter, Parmar heard a Radio National show that spoke about the rescue of Indian POWs in PNG. He called in, and said, “I am Chint Singh’s son.”

From there it was as if the story unravelled itself to Parmar. He travelled across Australia meeting many of the men who had known his dad, a sociable person and great communicator who had charmed everyone he crossed paths with after his rescue.

Many of them recalled Chint’s thank you speech on behalf of his men, in which he said touchingly, “We are reborn.”

“I am amazed at the warmth with which they spoke of my dad,” Parmar revealed. “It was a very proud moment when in 2004, they invited me to march with them on Anzac Day.”

Chint Singh returned to Australia in 1970, invited by the Australian government as Indian representative to mark the 25th anniversary of Japanese surrender celebrations at PNG. Sadly, the plinth that was erected has since been washed away in flood waters.

Yet Chint’s signature can be seen, alongside those of others, on a surrender flag that is today held at the Australian War Memorial. It was carried by the commander of the Japanese forces in New Guinea, Lt Gen Adachi, on 11 Sept 1945.

To purchase Narinder Singh Parmar’s book, head to https://www.shawlinepublishing.com.au/

The Indian launch will be held on 15 Nov at Rajasthan by the 2nd Dogras, Chint Singh’s regiment, as it commemorates OP Hill Day, a significant victory in the 1965 Indo-Pak war.