When it comes to making a statement through art, New Delhi-based artist Mithu Sen is never one to mince her words. Funnily enough, she does so doing literally that; sardonic contracts penned in comic sans, the cheeky insertion of ‘un’ into every crevice of a word, the deliberate, chaotic estrangement of mundane words in glitchy poems.

It’s gleeful and reckless. It’s playful and confronting. It’s ‘linguistic anarchy’, and mOTHERTONGUE, the latest Mithu Sen exhibition from the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) delivers this in spades.

A multidirectional mind-map

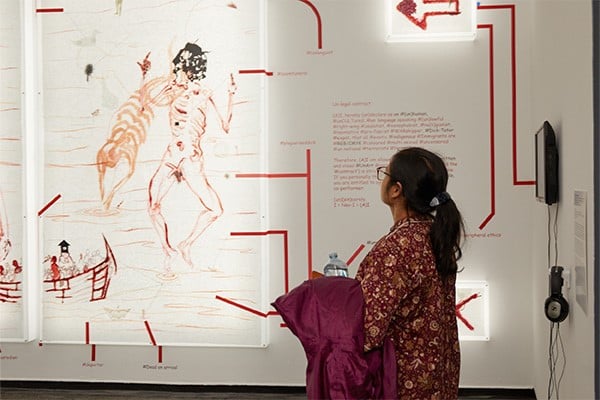

Structured as an ‘illuminated mind-map’, the exhibition traverses Sen’s two-decade oeuvre, past and present converging across the surfaces of the ACCA space. The walls are inscribed with text annotations, a non-sequitur footnote from the artist, and a continuous LED strip integrates the ACCA’s architecture into the experience.

The result is a ‘constellation of images and word associations’ resisting easy consumption, a tangled network of connections immersing you in Sen’s multiversal practice.

“Normally in museums when you see mind maps, they’re linear and chronological, whereas in this case it’s multidirectional,” explains ACCA Curator Max Delany. “Because Mithu’s work spans mediums, it really supplants any singular reading with multidirectional and multi-sensory registers.”

“Through the footnotes, contracts and use of language, she is involved in modes of direct address to the audience, often in first person singular – not speaking for others, but a position that is very much that of the artist’s voice,” he says.

Post-colonial lingual politics

Sen’s preoccupation with language began in 1997, when she migrated from West Bengal to Delhi to attend art school. Having only previously written Bengali poetry, she felt alienated in the cosmopolitan capital where English and Hindi dominated, and proficiency was associated with social position. This discomfort prompted her to deconstruct the very foundations of language in her works, examining how it’s used to gatekeep, isolate and reinforce power structures.

“‘Mothertongue’ is an emotional, sentimental word, but I tried to explore it here through the lingual anarchy position, as a primordial embodied space within our body. It’s a provocation and makes us curious,” said Sen in conversation at ACCA.

The questions mOTHERTONGUE poses resonate especially with the post-colonial lingual politics of India, and the discombobulating lingual domination experienced outside of the subcontinent.

“India has never had a national language,” she said. “The hegemony and hierarchy of these lingual politics around our social platforms is quite hardcore for me.”

A middle finger to the art world

Within the international art world, non-dominant cultures are often decontextualised or exoticised, with artists from the global south expected to create and behave a certain way.

Sen’s work delightfully and riotously ruptures this expectation, rebelling against the powers which dictate ‘acceptable’ art. It’s aggressive, visceral, sensual, and political – things which brown women don’t often ‘get to be’.

Sen’s graphic preoccupation with the body is case in point. Beauty and viscera are juxtaposed in Until you 206 and BYEBYEPRODUCTS!! BUYBUYPRODUCTS, the latter of which is ‘awash in virulent red’, a violent yet intimate meditation on her ‘signature style’. The notion of the artist putting blood, sweat, and tears into their work is literally manifested in Unbelongings, an embroidery of Sen’s own hair, and personal and political collide in Ephemeral affair, the artist’s penetrating gaze teetering between emotional suppression and colonial subjugation.

“Working very closely with the artist to centre the artist’s voice was very critical”, says Delany on navigating these expectations. “The annotations, contracts and mind-mapping are a form of choreography framing Mithu’s work within her own terms and her own language.”

Radical hospitality on stolen land

Perhaps the most ironic provocation towards the museological canon is found in MOU (Museum of unbelongings); a haphazard assemblage of trinkets which could just as easily be in your living room showcase languidly carousel inside a giant museum vitrine.

The carnivalesque spectacle endowed on sentimental objects which Sen has amassed over the years is a powerful stab at what’s considered ‘fit for display’ in museums and invites reflection on museums repatriating objects stolen from cultures around the world.

It’s a statement pertinent to Australian audiences, who are the first in the world to see such a retrospective of Sen’s work.

“There’s a lot of interest in Mithu’s work here,” says Delany. “I think her engagement with colonial histories, questions around language and the baggage and questions around identity are also questions which are very much at the heart of contemporary Australian practice at the moment.”

“We’ve had wonderful engagement with the show; people are spending a lot of time with it. Lots of people are coming back for return visits, and lots of rich conversations have resulted.”

Whether it’s the Un-acknowledgement that begins the exhibition, or contracts declaring the terms of reference and engagement next to each piece, mOTHERTONGUE constantly twists the relationship between spectator, institution, and artist, ‘radical hospitality’ which has startling polysemy.

It’s art that unsettles, that’s difficult to define, that deconstructs perspective through it’s ‘unSensored’ approach.

Sen herself best captures this sentiment in conversation with ACCA: “Everyone should admit and acknowledge those erased and hidden points that we see but don’t see. Until something is said to our face, we don’t see it, we are blind.”

mOTHERTONGUE is on display at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), 113 Sturt Street Southbank, until 18 June 2023.

READ ALSO: Sutr Santati: Then. Now. Next: A must-see at Melbourne Museum