“How do I know if the oil temperature is right?” a young Sapna Ajwani once asked her aunt Sheila.

The response was simple yet poetic: “The oil will sing to you.”

This evocative moment captures the essence of South Asian cooking – where intuition and sensory connection take precedence over written recipes.

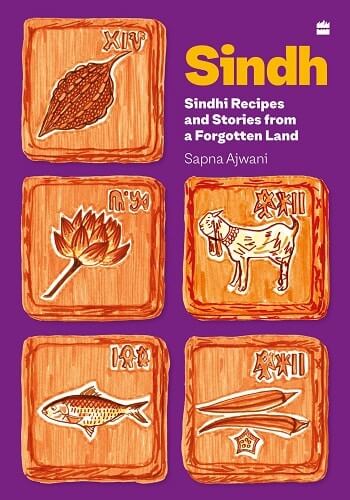

In her latest book, Sindh: Sindhi Recipes and Stories from a Forgotten Land (HarperCollins), culinary expert and storyteller Sapna Ajwani weaves together the rich tapestry of Sindhi history, culture, and cuisine. The book is not just a collection of recipes; it is an intimate narrative that reflects the Sindhi community’s resilience, especially in the aftermath of Partition. Drawing from her own family’s journey, Sapna recounts how her grandfather Tolaram led her family across borders to Rajasthan, carrying with him not only their belongings but also their culinary traditions.

“Despite the trauma of leaving everything behind, my family never forgot the kindness of their Sindhi Muslim neighbours who shielded them from violence until the day they left,” the author tells Indian Link. “Even as they embraced a new life, they never severed their bond with the land they had left behind. Within the privacy of their homes, they kept Sindh alive – through the food they cooked, the language they spoke, and the stories they lovingly passed down.”

“Despite the trauma of leaving everything behind, my family never forgot the kindness of their Sindhi Muslim neighbours who shielded them from violence until the day they left,” the author tells Indian Link. “Even as they embraced a new life, they never severed their bond with the land they had left behind. Within the privacy of their homes, they kept Sindh alive – through the food they cooked, the language they spoke, and the stories they lovingly passed down.”

For Sapna, food is memory, identity, and heritage. She describes herself as having a “food gene,” with her childhood memories steeped in the aromas and flavours of home-cooked meals. Unlike many households of the time, cooking in Sapna’s family wasn’t confined to women – it was a shared experience. This unique upbringing is central to her storytelling, which is as much about the food as it is about the hands and hearts that prepare it.

Mumbai-based Sapna moved to the UK in 2005, where she worked in financial services for several years. Around this time, she realised how the Sindhi cuisine had become “almost esoteric”. This set Mumbai-based Sapna on a mission: “I took a break from corporate life because I felt that hardly anyone seemed to know about us or our culture. People assumed Sindhi food was limited to Sindhi Kadhi and Dal Pakwan. The misconceptions ran deep. That’s what drove me to start this journey – to tell our story through food.”

In 2016, she established her supper club, SindhiGusto, to promote and spread awareness about the Sindh region. This book is an extension of that.

With anecdotes and insights that celebrate Sindhi language and flavours, Sindh offers readers a journey through the refugee Sindhi experience, where food became the anchor for a displaced community to preserve their identity and recreate a sense of home.

A remarkable cuisine

Sindhi cuisine, Sapna Ajwani shares, stands out for its historical and cultural influences, particularly those from Ancient Persia.

“This connection is unsurprising, given that Sindh was once a satrap under the Achaemenid and Sasanian empires. Later, in the 7th and 8th centuries CE, Sindh also became a refuge for many fleeing the Umayyad Caliphate,” she explains.

These influences are evident in both cooking techniques and ingredients.

“Take, for instance, our everyday rice: it is always cooked with salt and ghee. Profuse dose of black cumin (jeeri in Sindhi), herbs such as dill, fenugreek, mint, sorrel. In fact, many Sindhi recipes begin with the prefix Sai, meaning green, reflecting our reliance on herbs as the very foundation of our cooking. Unlike some other regional cuisines in India, our use of spices is notably restrained; several dishes are built around just two key spices – green cardamom and black pepper – highlighting the ingredient’s natural flavours.”

Sindhis love meat, fish and unique ingredients like lotus stem (bhee). Among these, pallah fish (hilsa/ilish) holds a special place in their hearts. Sapna shares why: “This reverence is deeply tied to our spiritual heritage; Jhulelal Saeen, the beloved Sindhi saint, is often depicted seated on a lotus flower mounted on a palla, the myth being that the fish swims upstream to pay homage to the Saint.”

Adapting to local circumstances

Displacement after Partition forced many Sindhis to start anew with very little. And so, adaptation also defined their cuisine.

“For example, seyal mani, traditionally made with leftover rotis, was reinvented with pav, the local specialty,” Sapna explains. “Our beloved lotus stem, a root vegetable synonymous with Sindhi cooking, was irreplaceable in its taste – especially those grown around the Indus delta. But since the quality wasn’t the same in new lands and bhee could be expensive, we began using potatoes as a substitute.”

Similarly, kachalu tuk (arbi) became alu tuk (potato). Even palla, the prized fish of Sindh, was replaced with locally available varieties by those who settled in coastal regions. Use of tomato and red chilli has become more prevalent now after the Partition. Sindh was a water scarce region, and tomato is a water guzzling fruit. That water scarcity also gave rise to cooking techniques such as ‘seyal’ in which a lot of watery aromatics are added to start with and no additional water is ever added.”

But hardships didn’t mean that Sindhis would compromise on taste.

“Even a simple meal of rice and lentils was elevated with crunchy accompaniments like fried dried vegetables – bitter gourds, apple gourds (kachri) – or the unmistakable Sindhi papad crushed over the top. This ethos of adding oomph to every dish, no matter how basic, is an enduring hallmark of Sindhi cuisine, a testament to the community’s indomitable spirit,” Sapna adds.

Holding identity close

There is a significant Sindhi community in Australia, especially since 2016, primarily settled in Sydney and Melbourne. What role does food play in keeping their cultural identity alive even today?

“We may move to a new country, learn the local language, even dress like them, but at the end of the day even if we were to have other mewas (as we call all rich and luxurious food) to eat, we will always choose to go home and eat sai bhaji ain khichri or phote mein gosht ain mani (green cardamom goat/lamb) and nothing else will cut it,” Sapna Ajwani replies candidly.

READ ALSO: Sindhi khorak and other sweetmeats for a multicultural Diwali