It was 700 of us in the Adelaide Convention Centre, and we were all laughing and crying at the same time, thanks to Anh Do. Who would have thought listening to a keynote address would end up like this, and that too one delivered by a comedian. But Anh Do is much more than a comedian – perhaps motivational speaker is a better description.

Tears trickling down my face, I was relieved to see my neighbour was no better, smudged eyeliner and what not!

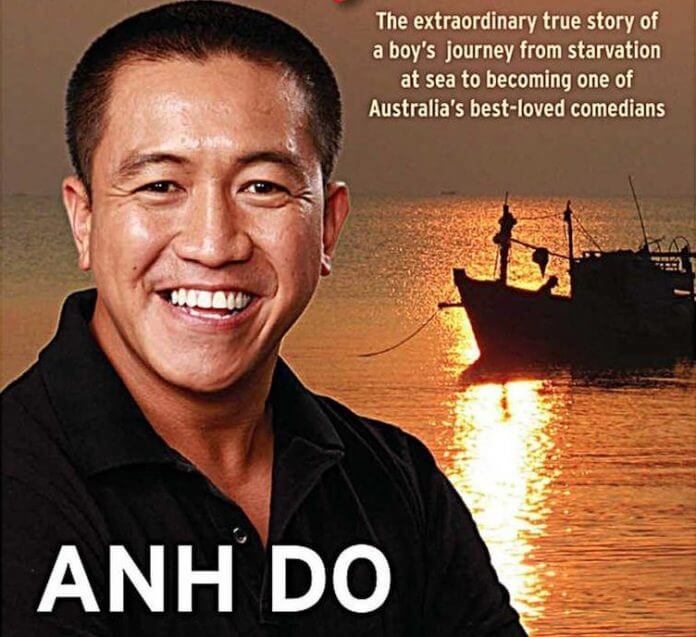

There we were, blotting up the words of Anh Do, the ‘happiest refugee’ and multicultural icon. If you’ve read Anh Do’s acclaimed 2010 book (The Happiest Refugee), you’ll know the story. Impoverished family leaves war-torn Vietnam on a crowded leaky boat, fighting the elements (and a pirate attack). They arrive in Australia, only to see their troubles continue as they settle in Yagoona. Dad can’t take the pressure and abandons the family, leaving Mum to raise three kids alone.

It is a touching tale, but told with a large comedic overlay, so that listeners (and readers) are left crying and laughing alternately.

It occurred to me that Anh’s recount is something we can all identify with as migrants, even though our own transition may have been smoother. As I learn more about fellow migrants –not just Indian migrants – the cross section of the struggles they encounter is formidable. International students who have not been provided an honest impression of the cost of their studies; well-settled couples that migrated without jobs and subsequently got thrown into the deep end; even fresh graduates who boarded the plane in search of better jobs and lifestyle but ended up with no luck… to list just a few of the many affected!

And talk about acculturation – where it takes a while for every new migrant to get used to how Sydneysiders talk, gesture, eat and even greet; and be embarrassed while we get accustomed to it all!

If it was Yagoona for Anh, it can be different suburbs for different ethnic communities in Sydney. Many subcontinentals start their lives in Western Sydney. The parallel social set up there – with spice shops, eateries, sporting grounds, cultural get-togethers and even schools that are populated with the kids of young migrant families – fosters a totally different culture compared to that of the mainstream. Second generation kids face much pressure to make it big in their lives; just like Anh Do signed up to be a lawyer, thinking that it would earn him the best of pay checks.

Second generation kids face much pressure to make it big in their lives; just like Anh Do signed up to be a lawyer, thinking that it would earn him the best of pay checks.

Many other things from Anh’s story rang familiar bells within me. He recalled how his parents had spent pretty much all their money buying warm clothes for the family, but it was summer when they landed. I took me back to my own first winter in Australia. Coming from a part of India with no huge fluctuations in the weather, I had no clue whether I was dressed less or more for the cold weather. And thus, I ended up either too cold or too hot. With the kids, I continued to struggle with their apparel as well – some days the poor things shivered, and other days they sweated in winter, until I worked out the happy medium.

And then come the cultural conflicts. Anh hilariously talked through how he brought his Vietnamese family to his engagement party which was held at his girlfriend’s home in the affluent northern suburbs. As part of the groom’s party, a suckling pig was carried in with pride, as the Vietnamese do traditionally. What was his mum’s thought when she saw the mansion – we should have brought a bigger pig!

Amidst the ripples of laughter, Anh had brought home the point about second-generation migrants who get entangled in the web of conflicting views and sentiments.

One of my own girlfriends told me recently, “My parents don’t approve of me going to late night parties, but I am being seen as antisocial at work because I don’t hang out with the colleagues on, say, Friday nights.” Or when newly enrolled youngsters at Uni have commented, “I am only used to Western Sydney, the university in central Sydney kind of intimidates me.”

Anh also talked about reconciling with his estranged father who has now taken another wife. We see more of it too in pour own community; extramarital relationships are increasing, with the freedom provided by a liberal Western society, but it often ends in catastrophe. No judgements here, but reports of divorces and even ‘entitlement’ murders have indeed gone up in our community.

The price to pay while we move into liberal societies can be much: whilst it is not always advisable to hang by unstable domestic relationships, one might wonder if the aggravating complications could be due to the loosely attached bonds.

Anh gave us a firsthand narration of the perils of displacement from the home-country, uprooting from comfort zones, challenges, struggles to start a new life in an exotic land when neck deep in poverty, and an account of how it takes generations to settle into a different culture.

The price to pay while we move into liberal societies can be much: whilst it is not always advisable to hang by unstable domestic relationships, one might wonder if the aggravating complications could be due to the loosely attached bonds.

One thing is for certain. Anh Do was not just telling his story, he was telling my story as well. And in all probability, it is your story too.