There have been occasional debates and discussions related to the use of these two names — India and Bharat — in official documents and discourse.

The term “India” is often associated with the country’s colonial past and is the internationally recognised name. On the other hand, “Bharat” has deep cultural and historical roots in India’s ancient texts and traditions.

The recent decision by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led government at the Centre to prioritise the use of “Bharat” over “India” has sparked debate over the nation’s identity and history.

The opposition has alleged that invitations to the G20 Summit dinner, sent by Rashtrapati Bhavan, featured the term ‘President of Bharat’ rather than the usual ‘President of India.’

This has sparked speculation that the government might introduce a resolution to officially rename India as Bharat during the upcoming special session of Parliament, which is being convened on September 18.

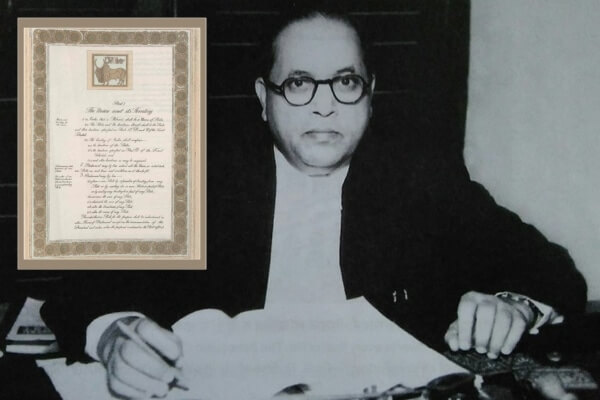

September has consistently been a month of debates for many years, and this can be traced back to September 1949 when there was intense discussion regarding the phrase ‘India, that is Bharat…’. This debate followed the establishment of a committee on August 29, 1947, by the Constituent Assembly, with BR Ambedkar as its chairman, to draft the Constitution.

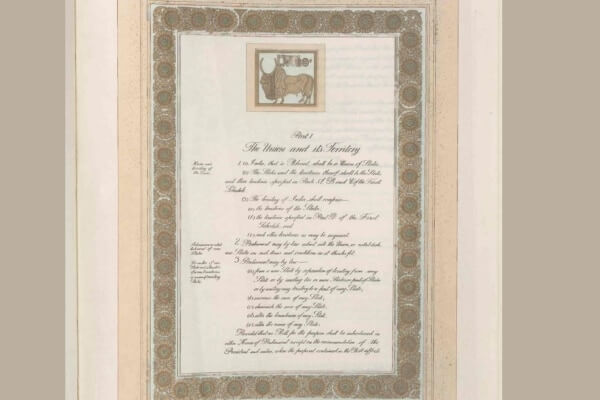

In 1948, the Draft Constitution of India began with Article 1, stating ‘India shall be a Union of States.’

During the Constituent Assembly discussion, some members suggested alternatives like ‘Bharat,’ ‘Bharat Varsha,’ and ‘Hindustan’ for ‘India.’

A year later, in September 1949, the Assembly revisited the issue to decide on the Union’s name.

Ambedkar, on behalf of the Drafting Committee, moved an amendment proposing to change Article 1 of the Draft Constitution to ‘India, that is, Bharat shall be a Union of States.’

It appears that the Drafting Committee took onboard demands to include ‘Bharat’ in the clause. Interestingly, the Committee retained ‘India’.

However, the members found the overall phrase – ‘India, that is, Bharat’ – undesirable.

But at the end of the debate, Assembly members accepted Ambedkar’s amendment. And the Constitution of India 1950 opened with ‘India, that is Bharat, is a Union of States’.

The debate over “India” vs. “Bharat” is not just a linguistic quibble; it reflects the larger struggle to define India’s identity in a rapidly changing world.

As the nation evolves, it’s essential to recognise that both “India” and “Bharat” have their place in the mosaic of this diverse and vibrant republic.

We refer to our country as India in English and as Bharat in other Indian languages. Even in Dravidian languages it is Bharata in Tamil, Bharatam in Malayalam and Bharat Desam in Telugu.

In Hindi, the Constitution is referred to as ‘Bharat ka Samvidhan’. And Article 1 is, ‘Bharata arthat India, rajyon ka sangha hoga’.

The term “Bharat” has ancient origins, found in Hindu texts like the Mahabharata and Manusmriti. Advocates of ‘Bharat’ argue it represents the region’s rich history and culture.

“India” isn’t a recent term either; it was derived from the Indus River, crucial in early regional civilisations, popularised by Greek historians, and later adopted during British colonial rule.

For decades, India and Bharat have both stirred deep emotions among patriots, symbolising the diverse and rich tapestry of a nation. These labels of pride, however, have increasingly become tools for narrow political objectives.

To understand the “India vs. Bharat” debate, one must delve into the historical context of pre-independence India. It was a land of stark contrasts, where urban centres epitomised modernity and progress, while rural areas remained deeply rooted in traditional values and agrarian lifestyles.

This divide was not just economic but also cultural and linguistic, giving rise to two distinct, yet interconnected, ideas of the nation.

The proponents of “India” argued for an identity that represented the urban and modern face of the country. For them, India was about embracing science and technology, industrialisation, and global engagement.

On the other hand, the champions of “Bharat” saw the nation through a different lens. They celebrated the deep-rooted cultural values, traditions, and spirituality that thrived in the countryside. To them, Bharat represented the soul of India, embodying timeless wisdom and a connection to the land.

The Preamble, which begins with “We, the people of India,” ultimately struck a balance by acknowledging both India’s modern aspirations and its traditional roots. It incorporated the principles of justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity, encapsulating the ideals of a pluralistic and progressive nation.

The BJP has already renamed cities and places that were linked to the Mughal and colonial periods. Last year, for instance, the Mughal Garden at the presidential palace in New Delhi was renamed Amrit Udyan.

Critics say that the new names are an attempt to erase the Mughals, who were Muslims and ruled the subcontinent for almost 300 years, from Indian history.

The Congress is leading a new opposition alliance that was recently formed with the aim of unseating Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the 2024 general election. The 26-party Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance, or INDIA, has made the potential name change an issue.

Read More: ‘India’ to ‘Bharat’: the name change gripping global media