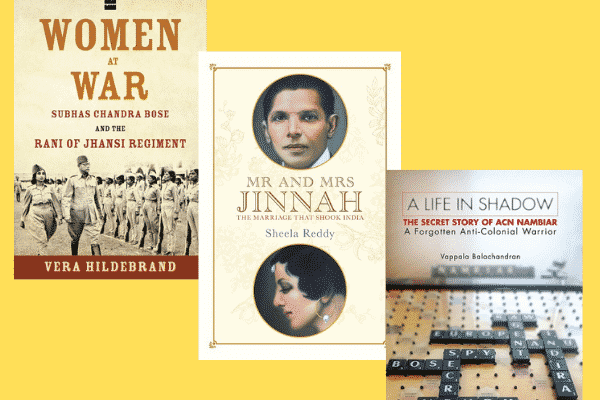

So many stories about India’s independence movement and partition still remain hidden, unsung and untold. So, it is with delight that I came upon three new books on that era that add so much to our rather limited and skewed understanding of what happened during those crucial decades before Independence.

ACN Nambiar, the ‘Indian renegade’

ACN Nambiar’s story is one of them. Haven’t heard of him? Neither had I until I read this remarkable biography of this unassuming man who was a journalist and freedom fighter, and a close associate of both Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhash Chandra Bose.

For most of his life, Kerala-born Nambiar lived in Europe. In the early and mid-1920s, he wrote columns for The Hindu – for which he had earlier apprenticed – from Berlin. He helped raise awareness in India and Europe on colonial exploitation through his columns.

This quiet, unassuming journalist rubbed shoulders with Indian communists, Bose and the Indian National Army as well as Nehru and his daughter Indira: yet he led a life away from the public gaze, as a trusted but discreet friend of them all.

To British intelligence agencies he was, ironically, a ‘notorious communist’ or a Nazi collaborator, ‘a tool in the hands of the Nazis’, ‘Indian Renegade’, and turncoat.

Nambiar was imprisoned after the war for collaboration with the enemy. He escaped to Switzerland and, against the wishes of Britain, was given an Indian passport by Nehru’s interim government. He then worked as a counsellor at the Indian Legation in Berne. After Independence, in 1951, Nambiar was appointed the first Indian ambassador to Germany.

Vappala Balanchandran, a former Indian intelligence officer and special secretary, met Nambiar in 1980. Balachandran was appointed to help an ageing Nambiar, on the orders of the then prime minister Indira Gandhi, who was concerned about the well-being of her father’s close friend.

Over the next few years, until Nambiar’s death in 1986, Balachandran spent time with him, caring for him and listening to the account of his life as a freedom fighter. In A Life in Shadow, Balachandran recounts Nambiar’s life through the latter’s accounts as well as letters and interviews with those who knew him.

In 2014, when the British government declassified several documents under its 30-year rule, it was discovered that they alleged that Nambiar was a Soviet spy during his time in Europe. Balachandran, who spent 13 years scouring through books and records, found no evidence anywhere that Nambiar was an active asset for any agency.

Two interesting conclusions jump out as significant in Balachandran’s biography of Nambiar: First, that contrary to popular conceptions, Nehru and Bose seem to have been on cordial and friendly terms. Nehru never doubted Bose’s patriotism, nor did he harbour any hatred for him. Bose, for his part, acknowledged Nehru’s standing in the freedom struggle.

Second, all the leaders who came in contact with Nambiar trusted him implicitly, because he never misused his proximity to people in power. He never once took advantage of his closeness to the towering figures of the Indian Independence struggle, nor did he drop their names in his newspaper columns.

Indira Gandhi remained in touch with him throughout her life; she felt very comfortable with him, as he had been the “uncle” who had taken care of her and her education, as well as Kamala Nehru’s health, in Switzerland. When Indira came back to power in 1980, she inducted Kao, the founder of RAW, as the Senior Intelligence Advisor on Nambiar’s advice (Balachandran has reproduced the letter in his book).

Did politics ruin Jinnah’s marriage?

Could Jinnah’s personal life – and his rather tumultuous marriage to a Parsi socialite Ruttie – impacted his political beliefs? Could it have been partly responsible for Jinnah’s changing course during the freedom struggle? Senior journalist Sheela Reddy tries to answer this question in her book Mr and Mrs Jinnah: The Marriage That Shook India, (Delhi, 2017, Penguin/Viking).

Jinnah was 42 and Ruttie 18 when they married. The union of the reclusive and enigmatic Mohammad Ali Jinnah and the free-spirited Ruttie Petit, was not a match made in heaven. The unlikely relationship took 1918 Bombay by storm for Ruttie was the only daughter of Sir Dinshaw Petit, a wealthy Parsi friend of Jinnah, who married him against her father’s wishes. The marriage was much talked about, and took place in the heart of Bombay and became a scandal all over the country. Ruttie was taken to court and the marriage caused so much fury and agitation among the Parsis (she converted to Islam before marrying Jinnah) who declared a Parsi version of a fatwa against the couple.

This was followed by a Muslim vs Parsi newspaper controversy. What followed this was Ruttie’s social isolation from her community and family, and at the same time, increasing alienation from her much older husband Jinnah, who was becoming preoccupied with politics and the law.

Ruttie tried hard to make her marriage a success, but it was a struggle. Their marriage was a tragic love story. She was a high spirited, wealthy young girl falling in love with a public hero; her break with everyone and everything from her past; her crushing disappointments; her descent into darkness – their marriage turned sour as Ruttie was unhappy that her husband’s devotion to work left him little time for her.

By mid-1922, Jinnah was becoming involved in Indian politics, which made him even busier. She walked out of the marriage, and died a lonely death at the age of 29. There’s speculation she may have died from an overdose of a drug she had been taking to combat a painful intestinal ailment.

Interestingly, the author quotes Indian diplomat MC Chagla’s belief that when Jinnah’s unmarried sister Fatima re-entered Jinnah’s life the day Ruttie died – never to leave his side again – it was the beginning of Jinnah’s transformation from a secular leader of Hindu-Muslim unity to an advocate of the two-nation theory. Reddy suggests that one reason could be found in his personal life.

What tempted Sheela Reddy to write the book was the dearth of information regarding Jinnah’s personal life and marriage. The work draws from several letters written by Ruttie and Sarojini Naidu that Reddy discovered during her research in Delhi (Nehru Library), Mumbai and Karachi. There was a whole sheaf of letters from Ruttie, around a hundred pages, which dated back to when she was 15 and ended abruptly a year before her death in 1929. Reddy said she had Padmaja and Leilamani Naidu (Sarojini Naidu’s daughters) to thank for as they had preserved those letters for posterity.

There are some interesting that tell us a lot about Jinnah: such as Ruttie’s rousing speech in the Ghatkopar Town Hall in Mumbai, which didn’t go down well with Jinnah. Reddy claims that after that speech, Ruttie took care to never make herself conspicuous in the political sphere. Later, when his daughter Dina wanted to marry Neville Wadia, Jinnah did not want to have his only child marry a Parsi Christian – it would have been a serious political embarrassment. “He tried to dissuade her but finding her adamant, Jinnah threatened to disown her. Instead of relenting, she moved into her grandmother’s home, determined to go ahead with the marriage,” writes Reddy.

The author quotes Urdu writer Saadat Hasan Manto to show that Jinnah took Dina’s defiance very badly: “For two weeks, he would not receive visitors. He would just go on smoking his cigars and pacing up and down in his room. He must have walked hundreds of miles in those two weeks,” Manto wrote.

READ ALSO: Partition Voices: Untold British Stories (Excerpt)

Bose’s warrior women

In 1943, Subhas Chandra Bose created the all-women’s Rani of Jhansi Regiment (RJR). The RJR fought under the 50,000 strong Indian National Army (INA) formed with the help of the Japanese forces, to free India from colonial rule. The women of RJR – called the Ranis – belonged to the Indian diaspora, mainly from Malaya, Singapore and Burma. Historians put the number of women in the regiment as high as 5,000.

Vera Hildebrand (Women at War: Subhas Chandra Bose and the Rani of Jhansi Regiment ) interviewed scores of women who served in the RJR while writing the book, including Captain Lakshmi, a leader and caretaker of the RJR recruits, to gauge what motivated the women to join, and what their experiences were. Her conclusion? That the motivations of the women who joined RJR were varied. Some were inspired by Bose’s nationalistic rhetoric; however, for most others from the Malay Peninsula, the reasons were somewhat different. They were swept by complicated emotions: ‘We worked together to do good’ said one; for most Ranis from Malaya and Singapore, the connections with India were much more tenuous. One said she joined the Ranis in order to become a nurse; others joined the RJR just in order to survive or earn a living or in order to get regular meals at a time when starvation was rife; or to escape forced marriages.

Many of the women who joined the Regiment from the large rubber estates in Malaya lived and worked under conditions that approached slavery. Sexual abuse by the mainly white estate managers was common. The Rani of Jhansi Regiment offered an environment where for the first time, the young women found themselves respected and free of the social stigma of “coolie” status. Now with their heads held high, they experienced a level of egalitarianism in the company of their Rani comrades that they had not known before. As one Rasammah explained, “We became soldiers for India’s freedom as well as for own liberty.”

READ ALSO: Khooni Vaisakhi: Poem from the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, 1919

Link up with us!

Indian Link News website: Save our website as a bookmark

Indian Link E-Newsletter: Subscribe to our weekly e-newsletter

Indian Link Newspaper: Click here to read our e-paper

Indian Link app: Download our app from Apple’s App Store or Google Play and subscribe to the alerts

Facebook: facebook.com/IndianLinkAustralia

Twitter: @indian_link

Instagram: @indianlink

LinkedIn: linkedin.com/IndianLinkMediaGroup