A public health activist and researcher in Arnhem Land takes up the fight against a deeply entrenched cultural practice

Following World No Tobacco Day not so long ago, a documentary film was released earlier this month that explores the problem of smoking in a remote Aboriginal community.

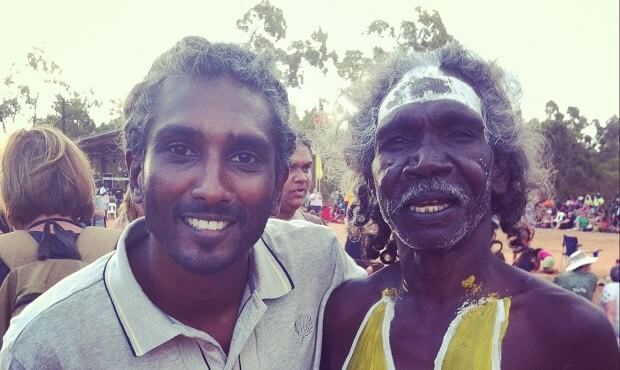

Produced and directed by Kishan Kariippanon, a doctor and public health communications researcher who lives and works in the Nhulunbuy in Arnhem Land, the film The Tobacco Story of Arnhem Land looks at the culturally entrenched practice of tobacco use in this community.

Smoking is the leading preventable cause of ill health and death among Indigenous Australians and contributes significantly to the gap in life expectancy. Previous efforts to stop smoking have not been successful. So Dr Kishan decided to take a different tack.

Inspired by Tamil film director Venkat Prabhu, Kishan has used the Tamil cinematic style to shoot this documentary.

“I like the way they show emotion in Tamil movies,” Kishan revealed to Indian Link. “I want Aboriginal kids to watch my film, absorb the story and its lesson, and share it”.

He has a practical approach to the smoking problem.

“It is ridiculous to expect people to quit when they have been smoking since they were children,” Kishan explains. “Smoking is ingrained in their culture; they even have a tobacco dance at funerals. My style is to take baby steps in changing behaviour – don’t smoke in front of grand-kids, don’t ask children to pick cigarettes for you, and don’t smoke in your house or your car where there are kids”.

Kishan Kariippanon is currently researching the interplay of social media and mobile phones amongst Yolngu (Aboriginal) youth, observing their use of Facebook and mobile phones, and how this could be used to promote their wellbeing.

Arnhem Land is one of the few areas in Australia where Aboriginals still live a traditional life.

So how did Kishan, a Malaysian with an Indian background, land in Nhulunbuy?

“I worked for three years at Darwin at the Centre for Disease Control, looking at sexual health and policies around young people. One of my aims was to help make the clinics more youth-friendly. During this time I realised that there was a lot of social media use by Aboriginal kids in remote communities. They do not have a TV or landline, but they do whatever they can to access Facebook and YouTube through their mobile phones. I was intrigued and decided to research this for my PhD,” Kishan says.

Speaking at TEDx Darwin, Kishan argued that promoting health to Indigenous youth needed a serious rethink. Social media and mobile technology could be put to good use to accomplish this, he suggested.

A doctor who heard Kishan’s talk at TEDx invited him to be part of his scabies project in Arnhem Land.

Shortly thereafter, Kishan moved with his family from the relative comfort of city life in Darwin to a tin-shed house in Nhulunbuy.

The move was crucial to his being accepted by the Aboriginal community.

“They felt that this guy must be serious, if he’s decided to move so close to us!” Kishan says with a laugh.

He adds with a twinkle in his eye, “I used my cooking skills to entice the elders. They loved my chicken curry, rice and pappadums!”

“Growing up in a multicultural society like Malaysia, and having the rich heritage of India, certainly gave me an advantage as some of the cultural protocols of the Aboriginals came naturally to me,” he continues.

Kishan’s earnestness in understanding the Aboriginal culture was evident and soon he had the trust of the Yolngu people. He even started learning their language by mixing with the locals. The more he understood the people, the more he was struck by the similarities of their culture and language to that of Asia.

“Specific Yolngu clans are distinctively similar to South Indians,” Kishan observed.

It has been a long journey spanning continents and remote corners for this intrepid man.

Volunteering in Siberia after high school in Malaysia, he stayed on to complete medical school in Russia. Soon he was packing his bags for Timor Leste, when the civil crisis broke in 2008, to volunteer as a doctor. Kishan’s multi-lingual skills proved very useful and he had a busy life at the clinic seeing 150 patients a day. But this was soon to change.

His keen observation skills helped uncover a human trafficking syndicate. When the number of young girls who came to test for HIV at the clinic reached 26, Kishan suspected that the girls were being trafficked. He took his hunch to the police. The perpetrators were caught and a massive ring from Timor Leste to Cambodia to Damascus to the Middle East, was uncovered. Thanks to him the young girls were saved, but it was no longer safe for him to remain in the country. Soon he was off to Melbourne to do a Masters’ degree in Public Health.

“And that was the end of my short clinical practice,” laughs Kishan, happily going wherever life has taken him.

Today, he is passionate about Aboriginal affairs.

When asked if ‘Closing the Gap’, the government program on reducing the 17-year life-expectancy gap between Aboriginal Australia and other Australians has worked, Dr Kishan is emphatic that it has.

“Only in the 1970s were Aboriginal people given citizenship rights. Before that they came under the Flora and Fauna Act! This segregation and other factors have had a long term effect on the psyche of people. ‘Closing the Gap’ is definitely a good start. Things are slowly getting better. The difference in culture is definitely a barrier. We need more participatory decision-making processes, a trans-cultural approach to solutions,” says Kishan, who now has a first-hand understanding of the issue.

For more about Kishan Kariippanon’s film The Tobacco Story of Arnhem Land, visit www.miwatj.com.au