Author Christos Tsiolkas questions, mocks and helps society fight the status quo, writes RAKA SARKHEL

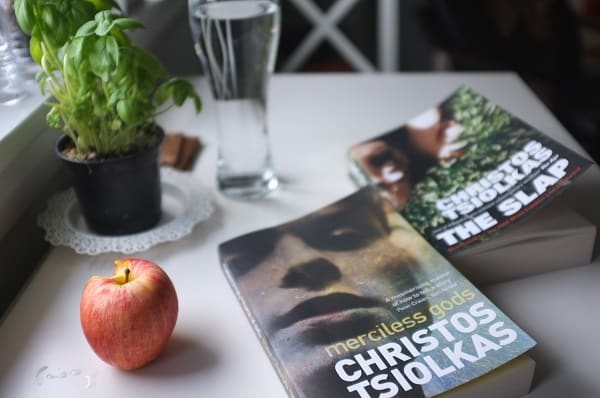

I first found Australian author Christos Tsiolkas at a time when I had just relocated to Sydney, along with my Indian baggage, and was still struggling to make a home in this huge multicultural patchwork. I picked up a copy of his Merciless Gods and chuckled at the relevance and resonance of the title in my life as the merciless gods above (pun intended) played cosmic chess with us as their pawns and chose our destinies and dilemmas for us.

Tsiolkas spoke at this year’s Jaipur Literature Festival at the session entitled ‘Refiguring Masculinity’. The thoughts he offered as part of the passionate discussion gives us an insight into the minds of his characters and the circumstances that they find themselves in.

A short story collection, Merciless Gods opens with a gathering of friends who believe themselves to be special, only to realise that they are as “mundane and trivial as everyone else”. The book dissects the dynamics and the baggage in a collection of thinking individuals and that one Achilles heel that fractures the group. It is a story that has happened or will happen to all of us at some point in life.

Tsiolkas, with his Hellenic roots and an Australian identity, is much like the characters he weaves. They are a genetic soup and struggle with their identities, travelling in search of it and coming to terms with its amorphous forms. His scuffle with his true identity is vulnerably captured in ‘Petals’, the story of an immigrant prisoner which he wrote in Greek and then translated into unrefined English, perhaps to preserve the real voice.

“I learned to feel Australian by travelling to Europe,” Tsiolkas is quoted as saying. This is true for his characters and readers alike because isn’t that why we travel in the first place? To find ourselves; to fit and misfit. His young couples uproot themselves and travel to New York in search of fresh perspectives, and elderly couples journey to Petra in search of the antediluvian. He sums up the politics of the world in two sentences in the ‘The T–Shirt With A Fist On It’: “The proximity of the world in the northern hemisphere was startling, astonishing. If Australia was defined by the tyranny of distance, here was determined by its subjugation to proximity.”

Tsiolkas’ female characters too are vulnerable, honest, sensuous and intricate. At several points in the book, such as where the wife still shuts the door in front of her husband to take a pee, or where Amanda compares her lover’s thighs to the contours of a guitar, I stood in awe and wondered how Tsiolkas being a man (who loves another man) can effortlessly capture a woman’s coyness and insecurities.

“The best advice I got when starting as a writer was that you have to be bisexual. This has nothing to do with sexual orientation but rather being able to take on both the masculine and feminine mindsets,” says Tsiolkas. My question is answered.

At one point, he also talks about his incisive, argumentative mother who was denied an education, like other women of her times. I am inclined to believe that he gave her a voice in his story ‘The Hair of the Dog’, which unapologetically (and quite nonchalantly) begins with the words, “My mother is best known for giving blowjobs to Pete Best and Paul McCartney in the toilets of the Star-Club in Hamburg one night in the early sixties.”

The father or the father figure is also a very important aspect of the narrative psyche and the father-son bond and the role reversal are tenderly portrayed in ‘Saturn Return’ and ‘Genetic Material’. Tsiolkas shares that his father taught him to control rage, a masculine attribute, and also that one could be sensitive and still be a man.

His language is lucid and his metaphors real. He aptly reveals the fluid nature of societal structures (however rigid we want them to be), gender and identity itself. At times while reading, I would assume the gender of a character which he does not reveal. Tsiolkas often made me very conscious of my subjectivities and the baggage I carried around unknowingly. I questioned myself as he tried to question society’s smugness and complacency. That affirms the fact that he has accomplished what an author sets out to do. Ask the right questions. Answer. Ask some more.

A fresh look at gender identity

Reading Time: 4 minutes