NAPLAN is an excellent, though basic, beginning

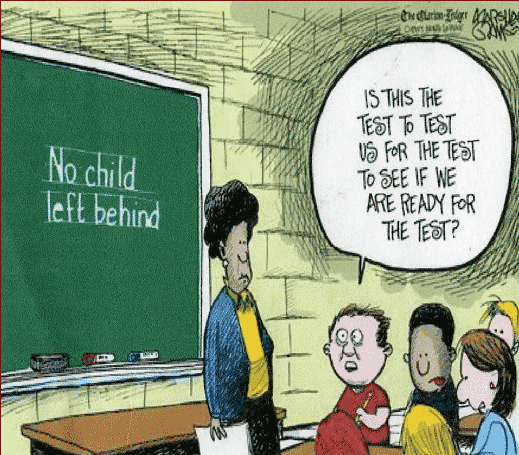

Basic national testing is on the agenda again amid some calls for it to be scrapped. Some parents do not let their children sit the tests, some educators have been criticised for teaching to the test, and there have been claims that children become anxious prior to the test. Moreover, a so-called ‘positive’ psychologist has stated that ‘NAPLAN is a complete failure’. This kind of extreme negative statement belies the truth about the test. Proponents of the tests emphasise the benefits of benchmarking performance and bringing accountability to teaching. They say the test is necessary for measuring national standards, identifying areas of weakness and ensuring that informed decisions are made about schooling. Ignoring the politics and focusing purely on assessment may be useful.

Educational assessment can never be properly characterised as wholly successful or wholly useless. Indeed characterising NAPLAN in such black or white terms does not model critical thinking skills. All assessment has some benefits and all assessment has limitations. For example, assessing basic literacy and numeracy standards allows the compilation of data about what children in Australia, at different stages in schooling, can achieve. Detailed reporting then allows parents and educators to target specific areas of weakness and make proper interventions, informed by evidence. As such, NAPLAN has been highly successful.

Assessment is even more beneficial when educators use the results of testing as a means of self-assessment, asking important questions such as, ‘What could I have taught better? How can I meet a wider range of needs? Are the students in my class benefitting from my approach to teaching? How could our system be more rigorous for a range of learners?’ This introspective approach by teachers and educational stakeholders to assessment is a necessary feature of professionalism and accountability. All assessment is two-fold, providing information for insight into both the educated and the educators.

Assessment suffers from weaknesses as it cannot ever provide a complete snapshot of a child’s abilities and so there is always a danger that the results of testing will be used to define a child by what they do not do, rather than by what they can do. Moreover, test design always involves a trade off between what is included or assessed and what is left out or ignored. The assumption with any assessment is that it ‘tests’ a body of knowledge, a unit of work and/or key skills. The reality of assessment is different. All people have relative strengths and it is possible for an assessment to underemphasise or even miss particular areas of skill, knowledge and ability. Of course, every educator, parent and educational bureaucrat would be wise to keep this in mind.

Of particular note with respect to the basic national NAPLAN tests is that the assessments are relatively narrow on the whole, constrained as they are to reading, writing, language conventions and numeracy. As a beginning point, they are useful for obtaining a baseline. This means these tests provide a useful data set from which to make some important decisions about literacy and numeracy interventions and support.

However, NAPLAN tests in their current iteration should be considered only a start. More robust national tests would be multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, include a technology base as well as elements of critical thinking, elements of creative thinking and scenario-based problem solving. Indeed, the question should be asked, in a rapidly changing world, how such tests could be expanded to also capture data on teamwork and social skills, understanding of others and the capacity to find information when faced with an open-ended problem.

Specifically, broader testing can be inclusive of each of the following: science and human health (including drug awareness, obesity and body image), mental health awareness, technological competence including critical awareness about technology use, civics and media. Broader testing could also examine elements of global awareness, cultural understanding and creative problem solving. Interdisciplinary thinking as exemplified by problems requiring logical reasoning, lateral thinking and also creative thinking would be highly relevant for older students. Perhaps national tests could be expanded to include Year 11.

Creative assessment could actually be ‘open book’ and integrate technology in the sense that students could work together in teams either within a school, or from different schools, to solve problems under time constraint. This would remove the element of schools competing and lead to more collaborative thinking – an essential feature in general society, the workplace and a globalised interconnected world.

Critics of the basic national tests will shudder at the thought of an increased breadth or scope for NAPLAN. However, the time has come to move beyond complaining about basic testing and ask what can be. Judicious focus and clever assessment can help children to adapt to a rapidly changing world.

As NAPLAN has never really been ‘high stakes’ testing, expanding the assessment is a low risk option to create resilient, critically thinking and creative students.